Kenneth J. Saltman -

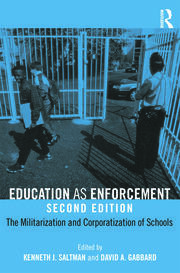

[Editors' note: This article is an excerpt from the "Introduction" to Education as Enforcement: The Militarization and Corporatization of Schools, a collection edited by Kenneth J. Saltman and David A. Gabbard, published by Routledge Press. ]

Military generals running schools, students in uniforms, metal detectors, police presence, high-tech ID card dog tags, real time Internet-based surveillance cameras, mobile hidden surveillance cameras, security consultants, chain link fences, surprise searches--as U.S. public schools invest in record levels of school security apparatus they increasingly resemble the military and prisons. Yet it would be a mistake to understand the school security craze as merely a mass media spectacle in the wake of Columbine and other recent high-profile shootings. And it would be myopic to fail to grasp the extent of public school militarization, its recent history, and its uses prior to the sudden interest it has garnered following September 11.

Military generals running schools, students in uniforms, metal detectors, police presence, high-tech ID card dog tags, real time Internet-based surveillance cameras, mobile hidden surveillance cameras, security consultants, chain link fences, surprise searches--as U.S. public schools invest in record levels of school security apparatus they increasingly resemble the military and prisons. Yet it would be a mistake to understand the school security craze as merely a mass media spectacle in the wake of Columbine and other recent high-profile shootings. And it would be myopic to fail to grasp the extent of public school militarization, its recent history, and its uses prior to the sudden interest it has garnered following September 11.

This book argues that militarized education in the United States needs to be understood in relation to the enforcement of global corporate imperatives as they expand markets through the material and symbolic violence of war and education. As an entry into the themes of the book this introduction demonstrates how militarism pervades foreign and domestic policy, popular culture, educational discourse, and language, educating citizens in the virtues of violence. This chapter demonstrates how a high level of comfort with rising militarism in all areas of U.S. life, particularly schooling, prior to September 11 set the stage for the radically militarized reactions to September 11 that include the institutionalization of permanent war, the suspension of civil liberties, and an active hostility of the state and mass media toward attempts at addressing the underlying conditions that gave rise to an unprecedented attack on U.S. soil.

Militarized schooling in America can be understood in at least two broad ways: "military education" and what I am calling "education as enforcement." Military education refers to explicit efforts to expand and legitimate military training in public schooling. These sorts of programs are exemplified by JROTC (Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps) programs, the Troops to Teachers program that places retired soldiers in schools, the trend of military generals hired as school superintendents or CEOs, the uniform movement, the Lockheed Martin corporation's public school in Georgia, and the army's development of the biggest online education program in the world as a recruiting inducement. The large number of private military schools such as the notorious Virginia Military Institute (VMI) that service the public military academies and the military itself could be thought of as a kind of ideal toward which public school militarization strives. Military education seeks to promote military recruitment as in the case of the 200,000 students in 1,420 JROTC army programs nationwide. These programs parallel the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts by turning hierarchical organization, competition, group cohesion, and weaponry into fun and games. Focusing on adventure activities these programs are extremely successful as half (47 percent) of JROTC graduates enter military service.

In addition to promoting recruitment, military education plays a central role in fostering a social focus on discipline. In short, to speak of militarized schooling in the United States context it is inadequate to identify the ways that schools increasingly resemble the military and prisons. This phenomenon needs to be understood as part of the militarization of civil society exemplified by the rise of militarized policing, increased police powers for search and seizure, antipublic gathering laws, "zero tolerance" policies, and the transformation of welfare into punishing workfare programs. The militarization of civil society has been intensified since September 11, as conservatives and most liberals have seized upon the "terrorist threat" to justify the passage of the USA Patriot Act. As Nancy Chang of the Center for Constitutional Rights explains, the Patriot Act sacrifices political freedoms and dangerously consolidates power in the executive branch.

It achieves these undemocratic ends in at least three ways. First, the act places our First Amendment rights to freedom of speech and political association in jeopardy by creating a broad new crime of "domestic terrorism" and denying entry to noncitizens on the basis of ideology. Second, the act reduces our already low expectations of privacy by granting the government enhanced surveillance powers. Third, the act erodes the due process rights of noncitizens by allowing the government to place them in mandatory detention and deport them from the United States based on political activities that have been recast under the act as terrorist activities.1

As Chang persuasively argues, the Patriot Act does little to combat terrorism yet it radically threatens basic constitutional safeguards, most notably the freedom of political dissent, which is, in many ways, the lifeblood of democracy as it forms the basis for public deliberation about the future of the nation. The repressive elements of the state in the form of such phenomena as militarized policing, the radical growth of the prison system, and intensified surveillance accompany the increasing corporate control of daily life. The corporatization of the everyday is characterized by the corporate domination of information production and distribution in the form of control over mass media and educational publishing, the corporate use of information technologies in the form of consumer identity profiling by marketing and credit card companies, and the increasing corporate involvement in public schooling and higher education at multiple levels. The phrase Education as Enforcement attempts to explain these merging phenomena of militarization and corporatization as they are shaping not only the terrain of school but the broader society. The term refers both to the ways that education as a field is being transformed by these trends but also it refers to the extent to which education is central to the workings of the new forms that power is taking.

What I am calling "Education as Enforcement" understands militarized public schooling as part of the militarization of civil society that in turn needs to be understood as part of the broader social, cultural, and economic movements for state-backed corporate globalization that seek to erode public democratic power and expand and enforce corporate power locally, nationally, and globally. In what follows here I lay out these connections. Then, by reading news coverage of NATO's attack against Kosovo in relation to the shooting at Columbine High School, the latter half of this introduction shows how both events were driven by the same corporate-driven cultural logic of militaristic violence. I continue by discussing how the movement against militarism in education must challenge the many ways that militarism as a cultural logic enforces the expansion of corporate power and decimates public democratic power.

Educating to Enforce Globalization

Corporate globalization, which should be viewed as a doctrine rather than as an inevitable phenomenon, is driven by the philosophy of neoliberalism. The economic and political doctrine of neoliberalism insists upon the virtues of privatization and liberalization of trade and concomitantly places faith in the hard discipline of the market for the resolution of all social and individual problems. Within the United States neoliberal policies have been characterized by their supporters as "free market policies that encourage private enterprise and consumer choice, reward personal responsibility and entrepreneurial initiative, and undermine the dead hand of the incompetent, bureaucratic and parasitic government, that can never do good even if well intended, which it rarely is."2 Within the neoliberal view, the public sphere should either be privatized as in the call to privatize U.S. public schools, public parks, social security, health care, and so on, or the public sphere should be in the service of the private sphere as in the case of U.S. federal subsidies for corporate agriculture, entertainment, and defense.

As many critics have observed, globalization efforts have hardly resulted in more just social relations either in terms of access to political power or democratic control over the economy. While corporate news media heralded economic boom at the millennium's turn, disparities in wealth have reached greater proportions than during the Great Depression,3 with the world's richest three hundred individuals possessing more wealth than the world's poorest forty-eight countries combined, and the richest fifteen have a greater fortune than the total product of sub-Saharan Africa.4

According to the most recent report of the United Nations Development Programme, while the global consumption of goods and services was twice as big in 1997 as in 1975 and had multiplied by a factor of six since 1950, 1 billion people cannot satisfy even their elementary needs. Among 4.5 billion of the residents of the "developing" countries, three in every five are deprived of access to basic infrastructures: a third have no access to drinkable water, a quarter have no accommodation worthy of its name, one-fifth have no use of sanitary and medical services. One in five children spend less than five years in any form of schooling; a similar proportion is permanently undernourished.5

Austerity measures imposed by world trade organizations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund ensure that poor nations stay poor by imposing "fiscal discipline" while no such discipline applies to entire industries that are heavily subsidized by the public sector in the United States. While the official U.S. unemployment rate hovers around 5 percent, the real wage has steadily decreased since the 1970s to the point that not a single county in the nation contains one bedroom apartments affordable for a single minimum wage earner.6 Free trade agreements such as NAFTA (and the FTAA that aims to extent it) and GATT, have enriched corporate elites in Mexico and the United States while intensifying poverty along the border.7 Free trade has meant capital flight, job loss, and the dismantling of labor unions in the United States, and the growth of slave labor conditions in nations receiving industrial production such as Indonesia and China. But perhaps the ultimate failure of liberal capitalism is indicated by its success in distributing Coca-Cola to every last niche of the globe while it has failed to supply inexpensive medicines for preventable diseases, or nutritious food or living wages to these same sprawling shanty towns in Ethiopia, Brazil, and the United States. Forty-seven million children in the richest twenty-nine nations in the world are living below the poverty line. Child poverty in the wealthiest nations has worsened with real wages as national incomes have risen over the past half century.8 The effects of globalization on world populations are a far cry from freedom.

Neoliberalism as the doctrine behind global capitalism should be understood in relation to the practice of what Ellen Meiskins Wood calls the "new imperialism," that is "not just a matter of controlling particular territories. It is a matter of controlling a whole world economy and global markets, everywhere and all the time."9 The project of globalization according to New York Times foreign correspondent Thomas L. Friedman "is our overarching national interest" and it "requires a stable power structure, and no country is more essential for this than the United States," for "[i]t has a large standing army, equipped with more aircraft carriers, advanced fighter jets, transport aircraft and nuclear weapons than ever, so that it can project more power farther than any country in the world . . . America excels in all the new measures of power in the era of globalization." As Friedman explains, rallying for the "humanitarian" bombing of Kosovo, "[t]he hidden hand of the market will never work without the hidden fist--McDonald's cannot flourish without McDonnell Douglas, the designer of the F-15. And the hidden fist that keeps the world safe for Silicon Valley's technologies is called the United States Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps."10 The Bush administration's new military policies of permanent war confirm Wood's thesis. The return to cold war levels of military spending approaching $400 billion with only 1015 percent tied to increased antiterrorism measures can be interpreted as part of a more overt strategy of U.S. imperial expansion facilitated by skillful media spin amid post-September 11 anxiety. The framing of those events enabled not only a more open admission of violent power politics and defiant U.S. unilateralism but also an intensified framing of democracy as consumer capitalism. Who can forget the September 12 state and corporate proclamations to be patriotic and go shopping. Post-September 11 spin was a spectacularly successful educational project. Suddenly, in teacher education courses, students who would have proudly announced that they could see no relationship between U.S. foreign policy and U.S. schooling now proudly announced that teachers must educate students toward the national effort to dominate, control, and wage war on other nations who could threaten our economic and military dominance because we have the best "way of life," because "they are jealous of our freedoms," because "they are irrational for failing to grasp that our way of life benefits everybody." Yet, the new Bush military expenditures are part of a longer legacy of World War II military spending that has resulted in a U.S. economy that is, in the words of economist Samir Amin, "monstrously deformed," with about a third of all economic activity depending directly or indirectly on the military complex--a level, Amin notes, only previously reached by the Soviet Union during the Brezhnev era.11

The impoverishing power of globalization is matched by the military destructive power of the new imperialism that enforces neoliberal policy to make the world safe for U.S. markets. However, weapons are not the predominant means for keeping Americans consent to economic policies and political arrangements that impoverish the world materially and reduce the imaginable future to a repetition of a bleak present. Rather, education in the form of formal schooling and predominantly the cultural pedagogies of corporate mass media have succeeded spectacularly in making savage inequalities into common sense, framing issues in the corporate interest, producing identifications with raw power, presenting history in ways that eviscerate popular struggle, and generally shifting the discussion of public goods to the metaphors of the market.12

Though initially received as a radical and off-beat position by liberals and conservatives at the time of its promotion by Milton Friedman during the Kennedy administration, neoliberalism began to take hold with the Reagan/Thatcher era. Significantly, the Reagan era is also the origin of the landmark A Nation at Risk report published in 1983. This formulated a crisis of U.S. public education through the language of global business and military competition. It began, "If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war." The report suggested that there was a crisis of education requiring radical reform. Because the crisis was framed in economic and militaristic terms, the solution would be sought in those domains. This marked a turning point in the public conversation of American education. While such earlier initiatives as the GI Bill and Sputnik indicated a strong link between the military and education, what can be seen as new is the way that militarism was tied to the redefining of education for the corporate good rather than the public good. In other words, this marked a new conflation of corporate profit with the social good, the beginnings of the eradication of the very notion of the public. Corporate CEOs became increasingly legitimate spokepersons on educational reform. Such high-profile corporate players as Louis Gerstner of IBM began declaring that education needs to serve corporate needs. Increasingly, as David Labaree has noted, this trend marked a shift toward defining the role of schools as preparing students for upward social mobility through economic assimilation. So, while on a social level, schools were suddenly thought to exist for the good of the national economy, that is the corporate controlled economy, on an individual level, schools came to be justified for inclusion within this corporate-controlled economy.

The case of Michael Milken nicely exemplifies the relationship between the neoliberal redefinition of the goals of public schooling and the privatization movement. Upon release from prison for ninety-eight counts of fraud and insider trading that resulted in the milking of the public sector of billions of dollars, junk bond king Michael Milken immediately began an education conglomerate called Knowledge Universe with his old pals from investment bank Drexel. As he bought up companies engaged in privatizing public schooling, he declared on his website that schools should serve corporate needs. He was wildly lauded throughout the press by such respectable papers as the New York Times, and was declared a greater figure than Mother Teresa by Business Week for redeeming himself from a tainted past by such good works in education. In addition to Knowledge Universe, Milken established the Milken Institute that propagandizes neoliberal social policy, and he set up the Milken Family Foundation that funds research and lobbies for privatization of Israel's economy and education system through the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. He also funded Justus Reid Weiner's slanderous attack in Commentary Magazine on Palestinian human rights spokesperson and progressive intellectual Edward Said. Milken was instrumental in the growth to monopolistic proportions of Time Warner, which included Time's swallowing of Warner Brothers and Turner Broadcasting, and the growth of MCI. As Robert W. McChesney, Edward Herman, and others have shown, the radical consolidation of corporate media with its stranglehold on knowledge production has contributed significantly to the success of neoliberal ideology.13

Neoliberal ideals were not taken seriously until the 1990s, in part because of the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. This began a tide of claims that we live in the best and only social order. This is a social order marked by what Zygmunt Bauman calls the TINA thesis: There Is No Alternative to the present system.14 The TINA thesis was started by Francis Fukuyama's "End of History" argument and runs through Thomas Friedman's The Lexus and the Olive Tree with its circular logic: everyone in the world wants to be American because this is the best of all possible systems, and if anyone does not want to be American, this proves their irrationality and we must bomb them into realizing that this is the best of all possible systems. The dissolution of the Soviet system as a symbol of a possible alternative allows a growing insistence on the part of neoliberals that since the present order is the only order, then the task should be one of enforcing the ideals of the order, aligning institutions and social practices with these ideals. So for example, you get Washington Post columnist William Raspberry (who favors full-scale public school privatization) writing that scripted lessons may seem harsh but after all "it works."15 Such an instrumentalist approach to schooling, which overly relies on supposedly value-free and quantifiable measures of "success," fails to account for how efficacy needs to be understood in relation to broader social contexts, histories, and competing notions of what counts as valuable knowledge. So, for example, how did the canon championed by E. D. Hirsch, Jr., with his Core Knowledge Schools come to be socially valued knowledge? Whose class, racial, and gender perspectives does such knowledge represent? There are high social costs of measures such as scripting, standardization, and the testing fetish. Citizenship becomes defined by an anticritical following of authority; knowledge becomes mistakenly presented as value-free units to be mechanically deposited; schooling models the new social logic that emphasizes economic social mobility rather than social transformation--that is, it perceives society as a flawed yet unchangeable situation into which individuals should seek assimilation into the New World Order.

This criticism of instrumental schooling would seem not to be a terribly new insight. In education, the tradition of critical pedagogy that includes Freire, Apple, Giroux, and others made this critical insight a basic precept. However, what is distinct about instrumentalism under the neoliberal imperative is that prior taken-for-granted ideals of an education system intended to ameliorate, enlighten, and complete the individual and society no longer hold. For neoliberalism is not simply about radical individualism, the celebration of business, and competition as a virtue; it is about a prohibition on thinking the social in public terms. In the words of Margaret Thatcher "there is no such thing as English society," there are only English families.16 The insidiousness of the TINA thesis cannot be overstated. When there is no alternative to the present order then the only question is the method of achieving the goal--the goal being the eradication of anything and anyone that calls the present order into question. This is why it has been so easy following September 11 to discuss methods that are radically at odds with the tradition of liberal democracy in the war on terrorism. (It is no coincidence that the new war is declared on a method of fighting rather than an ideological opponent or another nation. Precisely because there is no alternative to the present order, the values, ideologies, and beliefs of the opponent are not discussable. Ethics can only be a matter of strategy.) Torture of prisoners, disappearances of suspects, spying on the population without limit, and an unprecedented level of secrecy about the workings of the government are a few of the proto-fascist developments that have been achieved within the first year since September 11. But the destruction of the trade towers did not itself make this rush to fascism possible so much as did the success of neoliberal ideology's prohibition on thinking, discussing, and creating another more just system of economic distribution, political participation, and cultural recognition.

Ronald Reagan entered office with plans to dismantle the U.S. Department of Education and implement market-based voucher schemes. Both initiatives failed largely due to teachers' unions and the fact that public opinion had yet to be worked on by a generation of corporate-financed public relations campaigns to make neoliberal ideals appear commonsensical.17 Despite this failure, in his second term Reagan successfully appropriated the racial, equity-based, magnet school voucher model developed by liberals to declare that the market model (rather than authoritative federal action against racism) was responsible for the high quality of these schools.18 What should not be missed here is that the real triumph of such rhetoric was to shift the discussion of U.S. public schooling away from political concerns with the role that education should play in preparing citizens for democratic participation. The market metaphors redefine public schooling as a good or service that students and parents consume like toilet paper or soap. Despite a history of racial and class oppression, that owes in no small part to the fact that U.S. public schooling has been tied to local property wealth and hence unequally distributed as a resource, public schooling has been a site of democratic deliberation where communities convene to struggle over values. Despite the material and ideological constraints that teachers and administrators often face, the public character of these schools allows them to remain open to the possibility of being places where curricula and teacher practices can speak to a broader vision for the future than the one imagined by multinational corporations. Thus, to speak of militarized public schooling in the United States, it is not enough to identify the extent to which certain schools (particularly urban nonwhite schools) increasingly resemble the military or prisons, nor is it adequate to point out the ways public schools are used to recruit soldiers. Militarized public schooling needs to be understood in relation to the enforcement of globalization through the implementation of all the policies and reforms that are guided toward the neoliberal ideal. Globalization gets enforced through privatization schemes such as vouchers, charters, performance contracting, and commercialization; standards and accountability schemes that seek to enforce a uniform curriculum and emphasize testing and quantifiable performance; assessment, accreditation (in higher education), and curricula that celebrate market values and the culture of those in power rather than human and democratic values. Such curricula and reforms are designed to avoid critical questions about the relationships between the production of knowledge and power, authority, politics, history, and ethics. While some multinational corporations, such as Disney in their Celebration School, and BPAmoco, with their middle-level science curriculum, have appropriated progressive pedagogical methods, these curricula, like ads, strive to promote a vision of a world best served under benevolent corporate management.

Selling War

JROTC and standard recruitment, prior to September 11, proved insufficient to keep the voluntary U.S. military stocked with enough soldiers to wield, in the words of Thomas Friedman, "the hidden fist that keeps the world safe for Silicon Valley's technologies and McDonald's."19 In fact, military recruiting in the United States has seen a crisis in the past few years. As of 1999 the army suffered its worst recruiting drought since 1979 with a shortage of 7,000 enlistees to maintain a force size of 74,500. The air force fell short by 1,5001,800, while the navy had to cut its target numbers and lower its requirements to make numbers.20 As recruitment target numbers have not been met, the military has invested heavily in a number of new advertising campaigns that radically redefine the image of the military and use "synergy" to promote the branches of the service in Hollywood films and on television. For example, navy ads use clips from the film Men of Honor, with military advertising preceding the film. Because the U.S. military must rely fully upon consent rather than coercion to fill its ranks, the military is portrayed in ads as fun and exciting, and the heroism of service is tied to the most sentimental depictions that play on childhood innocence and family safety to sell youth on the business of killing. The new campaign for the air force titled "Lullaby" promotes its new slogan "No One Comes Close." Quadrupling its advertising budget to $76 million (all the services are spending $11,000 per recruit on advertising),21 buying national television slots for the first time, and using a "brand identity" based approach, the new marketing seeks to induce recruitment by filling the airwaves with "value-based" advertising that emphasizes the "intangibles" of military service.22

An ad called "Lullaby," for example, shows home videos of happy children and their mother with a soft voice singing in the background. At the words "guardian angels will attend thee all through the night," the visual image shifts to an F-117 "stealth" fighter roaring across a dark sky. The only explicit appeal to recruits comes in the final second, when the Air Force's new slogan, "No One Comes Close," appears on a black screen followed for an instant by the words "Join Us."23

A central strategy of this campaign as well as the army's new "Army of One" campaign is to suggest a heroic exclusivity of service in this particular branch. All of the branches are following the Marine Corps' successful campaign that "portrayed enlistment as a chance to become a dragon-slaying knight in shining armor. The macho ads were designed to convince young people that joining the Marines was not merely a career choice but a powerful statement about what kind of adults they intended to become."24

The Air Force advertisement draws on Judeo-Christian imagery of an angry and protective techno-god. By joining the air force one can be the, protector of the innocent and approach the infinite power of the almighty--interchangeably God and the unmatchable techno-power of Lockheed Martin, Boeing, McDonnell-Douglas, and Raytheon. To be in the air force, the ad suggests, is to be in an elite and exclusive, powerful, and moral position. Another set of public service announcement ads aimed at adults seeks to "ensure that parents, teachers and other 'adult influencers' know about the educational programs so that they, in turn, can advise young people."25 These ads stress tangible rewards such as educational opportunities, high-tech skills training, and managerial expertise, which can later translate into cash in the corporate sector.

While the United States offers no public universal higher education program in civil society, it does so through the military. Ryan's statement about the higher calling of serving our nation is hardly a sentiment reserved for a conservative military establishment. Liberals and conservatives join in proclaiming the virtues of a military form of public service at a time when public spending goes increasingly for militarized solutions to civic social problems. These militarized solutions have translated into the United States having by far the largest prison system in the world with over two million inmates. Rapidly rising investment in the prison industrial complex, which includes for-profit prisons and high-tech policing, is matched by rapid privatization of the public sector.26 As U.S. citizens enjoy few of the social safety nets of public health care, education, or welfare, enjoyed by citizens of most industrialized nations, U.S. public institutions such as hospitals, schools, and social security are subject to the fevered call to privatize. At the same time that public investment in militarizing civil society has come into vogue, the world of the corporate class has discovered military chic. The first issue of Harper's Bazaar for the new millennium shows a serious looking fashion model goose stepping down the runway in uniform. The accompanying text sounds off: "Military Coup. Never thought you would crave camouflage? Think again . . . fashion's military scheme will have even the most resistant shopper succumbing to the latest protocol."27 The model's designer jacket is listed for $1,500, and the cotton skirt runs $370. Military chic for corporate elites extends to the nationwide trend for private boot-camp style exercise classes.

The same marketing strategies designed to lure recruits are used by weapons manufacturers Lockheed Martin and Boeing (along with a lot of money) to lobby the U.S. Congress to continue funding such miserably failed and unbelievably expensive and unnecessary weapons programs as the F-22 joint strike fighter and "Star Wars."28 As Mark Crispin Miller observes, the defense industry's advertisements not too subtly suggest that the public better fund the weapons projects or American family members will die in foreign wars and from terrorist attacks at home.29 The weapons manufacturers also use the ads to propose that peace is a result of heavy military investment, thereby obviating the need for social movements for peace such as those that influenced the end of the Vietnam War.

The new campaign for the army, "An Army of One," replaces the "Be All That You Can Be" slogan that was the number two jingle of the twentieth century behind McDonald's "You Deserve a Break Today."30 The "Army of One" campaign, like its predecessor, stresses individual self-actualization, yet goes a step further to insist upon the ideal of radical individualism. A lone recruit runs across a desert in full gear as troops pass in the opposite direction. Such images would seem to chafe against the necessity of self-sacrifice and teamwork, which more accurately characterizes the military. The new ads insist that every soldier is a hero, is an army. The promise is not merely one of becoming the "best" that one can be, a promise that implies there might still be someone better; the "Army of One" slogan promises that one incorporates the army into oneself, one renounces oneself and actually becomes the army with all of its power and technology. The Army slogan is consistent with the virtual tour offered by the marine corps. This tour begins by explicitly linking the militaristic renunciation of self to economic metaphors:

One must first be stripped clean. Freed of all the notions of self. It is the marine corps that will strip away the façade so easily confused with the self. It is the corps that will offer the pain needed to buy the truth. And at last each will own the privilege of looking inside himself to discover what truly resides there.31

One renounces oneself. One's body undergoes torments of the flesh. Yet this pain inflicted through training is currency that allows one to buy knowledge of one's new self. At the end of the tour one learns that self-renunciation, pain, the breaking and remaking, and ultimate purchase of self-knowledge results in the privatized social unit: "We came as orphans, we depart as family," concludes the marine tour.

Just as family restoration becomes the aim of war in the marine ad, so too does it appear in such blockbuster films as Saving Private Ryan, Men of Honor, Three Kings, and The Thin Red Line. The brilliant innovation of Saving Private Ryan was to make the goal of the good war not the protection of the public so much as the preservation of the private family unit. Saving Private Ryan simultaneously shifted democratic ideals onto the market metaphor. Freedom, we are told in the end of Saving Private Ryan, needs to be earned by individuals. When they have earned their freedom they can go home.

***

Within the climate of the innocent culture of violence the endlessly repeated images of collapsing twin towers were nearly seamlessly contextualized as a complete surprise, a fall from American innocence. Rather than confronting the problem with U.S. intervention in the Middle East, central and South America, and elsewhere as the original violence that has been some of the most brutal of the past century, the event was interpreted as unthinkable and irrational rather than as a political response, thereby justifying an escalation of violence in the Middle East, central and south Asia, and South America. In the declaration of permanent war not on a specific enemy but on a method of warfare, mindless vengeance trumps understanding the history of U.S. imperial violence overseas that brought about such brutal reaction. Moreover, the enemy's ideological commitments, basic values, and historical relation to the U.S. cannot be discussed as the ground of discussion in the war on terrorism is shifted to the methods of struggle. The enemy is anyone in the world who does not pledge allegiance.

Education is becoming increasingly justified on the grounds of national security. This can be seen in the Hart-Rudman commission that in 2000 called for education to be classified as an issue of national security, in the increase of federal funding to school security simultaneous with cuts to community policing, in the continuation of the Troops to Teachers program, as well as the original A Nation at Risk report. Why is this? It is tied to the attack on social spending more generally, the antifederalist aspect of neoliberalism, a politics of containment rather than investment, the political efficacy of keeping large segments of the population uneducated and miseducated, the economic efficacy of keeping funds flowing to the defense and high-tech sectors and away from the segments of the population that are viewed as of little use to capital. As well, the working class, employed in lowskill, low-paying service sector jobs, would be likely to complain or even organize if they were encouraged to question and think too much. Education and literacy are tied to political participation. Participation might mean that noncorporate elites would want social investment in public projects or at least projects that might benefit most people. That won't do. There is a reason that the federal government wants soldiers rather than say the glut of unemployed Ph.D.s in classrooms. Additionally, corporate globalization initiatives such as the FTAA seek to allow corporate competition into the public sector at an unprecedented level. In theory, public schools would have to compete with corporate for-profit schooling initiatives from any corporation in the world. By redefining public schooling as a national security issue, education could be exempted from the purview of this radical globalization that such agreements impose on other nations. Consistent with the trend, education for national security defines the public interest through the discourse of discipline that influences reforms that deskill teachers, inhibiting teaching as a critical and intellectual endeavor that aims to make a participatory citizenry capable of building the public sphere.

What to do? As Seymour Melman argues in After Capitalism, a central task for the future is to transform a war economy to a civilian one not only for former Soviet states but for the United States as well. Considering the ways that the global financial system maintains poverty and the military system produces war, a key task for educators is to imagine the role of education as a means of mobilizing citizens to understand and transform these systems toward a goal of global democracy and global justice. Militarized schooling can be resisted at the local level. Many activists and critical educators already do so. For example, Kevin Ramirez started and runs the Military Out of our Schools campaign that seeks to eject JROTC programs from public schools. Ramirez points out to parents, teachers, administrators, and newspaper reporters that school violence is an extension of social violence, which is taught. Like Ramirez, other civic and religious organizations work to eliminate military recruiting in schools. I have argued that militarized education in the United States needs to be understood in relation to the enforcement of corporate economic imperatives and in relation to a rising culture of "law and order" that pervades popular culture, educational discourse, foreign policy, and language. The movement against militarism in education must go beyond challenging militarized schooling so as to challenge the many ways that militarism as a cultural logic enforces the expansion of corporate power and decimates public democratic power. Such a movement against education as enforcement must include the practice of critical pedagogy and also ideally links to multiple movements against oppression such as the antiglobalization, feminist, labor, environmental, and antiracism movements. These movements and critical educational practice and theory need to form the basis for imagining and implementing a just future.

source: https://web.archive.org/web/20170829222449/http://clogic.eserver.org/2003/saltman.html

Notes

1 Nancy Chang, Silencing Political Dissent: How Post-September 11 Anti-terrorism measures threaten our civil liberties (New York: Seven Stories, 2002).

2 Robert W. McChesney "Introduction," in Profit Over People Noam Chomsky (New York: Seven Stories Press, 1999), 7.

3 "Since the mid-1970's, the most fortunate one percent of households have doubled their share of the national wealth. They now hold more wealth than the bottom 95 percent of the population." "Shifting Fortunes," Chris Hartman, ed., "Facts and Figures" (September 18, 2000), available at <http://www.inequality.org/factsfr.html>. In a report to the World Bank's Board of Governors, James D. Wolfensohn attests, "Across the world 1.3 billion people live on less than $1 a day; 3 billion live on under $2 a day; 1.3 billion have no access to clean water; 3 billion have no access to sanitation; 2 billion have no access to power." "The Other Crisis," October 6, 1998 available at <http://www.worldbank.org/html/extdr/am98/jdw-sp/am98-en.htm>. In the United States alone, "by far the richest country in the world and the homeland of the world's wealthiest people, 16.5 per cent of the population live in poverty; one fifth of adult men and women can neither read nor write, while 13 per cent have a life expectancy shorter than sixty years." Zygmunt Bauman, The Individualized Society (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2001), 115.

4 Bauman, The Individualized Society, 115.

5 Bauman, The Individualized Society, 114.

6 "Index," Harper's Magazine (July 2000).

7 "According to data from the 2000 consensus, fully 75 percent of the population of Mexico lives in poverty today (with fully one-third in extreme poverty), as compared with 49 percent in 1981, before the imposition of the neoliberal regimen and, later, NAFTA. Meanwhile, the longstanding gap between the northern and southern regions, as manifested in poverty, infant mortality and malnutrition rates, has grown wider as the latter has borne the brunt of neoliberal adjustment policies. Chiapas, for example, produces more than half of Mexico's hydroelectric power, an increasing portion of which flows north to the maquiladora zone on the MexicoUS border. Yet, even including its major cities of Tuxtla Gutiérrez and San Cristóbal de las Casas, only half of Chiapanecan households have electricity or running water. Additional water sources have been diverted to irrigate large landholdings devoted to export-oriented agriculture and commercial forestry, while peasant farmers have suffered reductions in water and other necessities as well as an end to land reform, even as they have endured a flood of US agribusiness exports that followed the NAFTA opening. According to the Mexican government's own official estimates, 1.5 million peasants will be forced to leave agriculture in the next one to two decades, many driven northward to face low-wage maquiladoras on one side of the border and high-tech militarization on the other." Jerry W. Sanders, "Two Mexicos and Fox's Quandary." The Nation (February 26, 2001): 1819.

8 John Williams, "Look, Child Poverty in the Wealthy Countries Isn't Necessary," International Herald Tribune (July 24, 2000). See also Chris Hartman, ed., "Facts and Figures": "nine states have reduced child poverty rates by more than 30 percent since 1993. These states include Tennessee, Michigan, Arkansas, South Carolina, Mississippi, Kentucky, Illinois and New Jersey. Michigan is a prime example of a national trend, in that even the recent dramatic improvement did not counter the losses of the previous 15 years, in which its poverty rate increased 121%. In California, the number of children living in poverty has grown from 900,000 in 1979, to 2.15 million in 1998.

9 Ellen Meiskins Wood, "Kosovo and the New Imperialism," in Masters of the Universe?, edited by Tariq Ali (New York: Verso, 2000), 199.

10 Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1999), 304, 373.

11 Samir Amin, Capitalism in the Age of Globalization (New York: Zed Books, 2000), 48.

12 Public schooling has come increasingly to be described in the language of monopoly, accountability, choice, and efficiency, and decreasingly described in the language of the public, the civic, community, and solidarity. For a longer discussion of the political use of market language in educational policy see Kenneth J. Saltman, Collateral Damage: Corporatizing Public School--a Threat to Democracy (Boulder, Colo.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000).

13 Robert W. McChesney, Rich Media Poor Democracy and McChesney and Edward Herman, The Global Media: The New Missionaries of Corporate Capitalism (Washington, D.C.: Cassell, 1997).

14 Zygmunt Bauman, In Search of Politics (Malden, Mass.: Polity, 1999).

15 William Raspberry, "Sounds Bad, but It Works," Washington Post (March 30 1998): 25A.

16 Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Malden, Mass.: Polity) 2000, 30.

17 McChesney "Introduction," 7.

18 See Jeffrey Henig's Rethinking School Choice (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994) for an excellent history of the appropriation of equity-based programs by privatization advocates.

19 Friedman, 373.

20 Steven Lee Myers, "Drop in Recruits Pushes Pentagon to New Strategy," New York Times (September 27, 1999): A1.

21 Robert Suro, "Army Ads Open New Campaign: Finish Education," Washington Post (September 21, 2000): A3.

22 Robert Suro, "Army Ads Open New Campaign: Finish Education," Washington Post (September 21, 2000): A3.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Noam Chomsky, Profits Over People (New York: Seven Stories Press, 1999).

27 Harper's Bazaar (January 2001): 35.

28 See Ken Silverstein's Washington on $10 Million a Day for a detailed expose on the way the lobbying industry ensures that weapons manufacturers keep politicians voting in favor of their projects.

29 Marketing Tomorrow's Weapons video produced by America's Defense Monitor.

30 News Services, "Army to Try New Advertising Maneuver to Boost Recruiting," Star Tribune (Minneapolis) (January 8, 2000): 12A.

31 Available at <http//:www.marines.com>.

###

Revised 10/15/2019

We live in a time of great destruction and grand economic opportunities and Latin America is no exception. In the global context, the US Empire is engaged in destructive wars ( Afghanistan , Iraq , Pakistan , Libya , Yemen , Somalia and Haiti ). In contrast China, India, Brazil, Argentina and other “emerging economies” are expanding trade, investments and reducing poverty. The European Union (EU) and the United States (USA) are in deep economic crises. The EU “periphery” ( Greece , Ireland , Portugal , Spain ) are totally bankrupt. The US “dependencies” in North America ( Mexico ), Central America and the Caribbean are virtual narco-states plagued by mass poverty, astronomical crime rates and economic stagnation. The US dependencies are plundered by foreign multi-nationals, local oligarchs and corrupt politicians.

We live in a time of great destruction and grand economic opportunities and Latin America is no exception. In the global context, the US Empire is engaged in destructive wars ( Afghanistan , Iraq , Pakistan , Libya , Yemen , Somalia and Haiti ). In contrast China, India, Brazil, Argentina and other “emerging economies” are expanding trade, investments and reducing poverty. The European Union (EU) and the United States (USA) are in deep economic crises. The EU “periphery” ( Greece , Ireland , Portugal , Spain ) are totally bankrupt. The US “dependencies” in North America ( Mexico ), Central America and the Caribbean are virtual narco-states plagued by mass poverty, astronomical crime rates and economic stagnation. The US dependencies are plundered by foreign multi-nationals, local oligarchs and corrupt politicians.

While there is an ongoing discussion about what shape the military-industrial complex will take under an Obama presidency, what is often left out of this analysis is the intrusion of the military into higher education. One example of the increasingly intensified and expansive symbiosis between the military-industrial complex and academia was on full display when Robert Gates, the secretary of defense, announced the creation of what he calls a new "Minerva Consortium," ironically named after the goddess of wisdom, whose purpose is to fund various universities to "carry out social-sciences research relevant to national security."

While there is an ongoing discussion about what shape the military-industrial complex will take under an Obama presidency, what is often left out of this analysis is the intrusion of the military into higher education. One example of the increasingly intensified and expansive symbiosis between the military-industrial complex and academia was on full display when Robert Gates, the secretary of defense, announced the creation of what he calls a new "Minerva Consortium," ironically named after the goddess of wisdom, whose purpose is to fund various universities to "carry out social-sciences research relevant to national security."