Nancy Townsley And Katie Sipos -

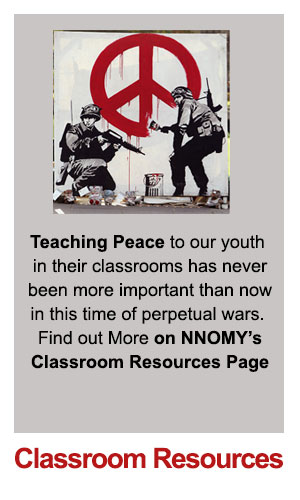

Local mom protests military visits to a Gaston school while a new Marine sees the service as 'another path' to success

Toting a red, white and blue protest sign, Barb Smith showed up outside Gaston Junior-Senior High School last Monday with a singular message: stop recruiting kids.

Toting a red, white and blue protest sign, Barb Smith showed up outside Gaston Junior-Senior High School last Monday with a singular message: stop recruiting kids.

On the first day back to class after winter break, Smith - a Forest Grove artist and mother whose son, Arlo Gann, is an eighth grader at the tiny rural school - decided she'd let the sign speak her mind for her.

'I seem to have run out of options with the district,' said Smith, who's upset that military recruiters' access to Gaston's junior high students, which was curtailed late in 2010, appears to her to have ramped up again.

'I thought [protesting] might be a way to find other people who think the way I do and get them to come on board,' said Smith. 'Maybe it will start a movement.'

Meanwhile, Marine Pfc. Sara Schaffner, a 2011 Forest Grove High School graduate, has set her sights on continuing a three-generation family tradition in the military. The athletic, strawberry blond 19-year-old joined the USMC when she turned 18 and is stationed in North Carolina, where she's training to become a deployment logistics specialist.

In December Schaffner was home in Oregon, working as a recruiter out of the U.S. Marine Corps Hillsboro office. She visited several high schools, including her alma mater, telling mostly juniors and seniors about her experiences in the service so far.

'[The] military isn't a bad option, especially if you don't have money for college. It's another path that will make you successful in the end,' she says.

Two women, a pair of perspectives

Smith and Schaffner are two different women from separate generations with opposite perspectives about military service - particularly the way young people are recruited in the first place.

In a time of relative peace, when America is active in a single war, Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan, recruiting by the Army, Air Force, Navy and Marines continues unabated. The Army even bumped up its maximum enlistment bonus from $20,000 to $40,000 last year in an effort to woo more recruits.

For Schaffner, joining the military represented a jumping-off point to get to where she wants to go, at least for now.

'I'm not yet sure if this is going to be a career,' she noted. 'I'm still feeling the waters.'

Still, she's proud to be a Marine, following in the soldierly footsteps of her grandfather, her father and her older brother, who's just finishing up his first tour of duty in Afghanistan.

'I wanted to do something with my life that wouldn't be just about me and would impact a lot of people for the better,' said Schaffner. 'I also wanted the honor, the image and the challenge.'

Smith, an admitted pacifist, has started an online blog, stoprecruitingkids.com, which she hopes will pull like-minded folks toward her side of the political spectrum. But even she knows there will always be a need for young people to fill out the ranks of the country's military forces, something that's supported by federal law in the form of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, formerly the No Child Left Behind Act.

'The law allows military recruiters to be in public secondary schools,' said Smith. 'But my kid's secondary school has seventh through 12th grades in it, so the 12- and 13-year-olds are free to visit with the recruiters.

'That is one thing I hope to change.'

The death in August of Navy corpsman Ryley Gallinger-Long of Cornelius provided a sober reminder that the men and women who sign up to defend our country sometimes pay the ultimate price.

But Joshua Woods said he knew what he was getting into when he signed up.

'My whole family's military,' said Woods, who graduated from Forest Grove High last spring. 'If something happens, if I get hurt or killed, I did my job and served my country and protected the people I love.'

Woods said he was familiar with the realities of military life since he'd had the opportunity to visit bases through his family's connections. After graduation, Woods committed to the Air Force, where he hopes to be trained as a security specialist or a psychologist. 'People are often surprised that there are jobs in the military that will set you up for a job outside - not just toting guns around,' said Woods.

The military offers an array of specializations, ranging from dental assistants to engineers and beyond, said Staff Sergeant Todd Miller of the Hillsboro Army Recruiting Office.

And Forest Grove School District assistant superintendent John O'Neill added that the service provides 'a viable alternative to college' as a potential career. '[It's] a means to develop some knowledge of skills [students] haven't had previously that could serve them in future endeavors,' he said.

Informed decisions

Surveys conducted by local high schools show that military-bound seniors such as Schaffner, Woods and Gallinger-Long are a minority, typically representing no more than 6 percent of a graduating class in western Washington County. Still, some community members want to ensure those students are making informed decisions about a vocation that has received less and less attention in the 10-plus years U.S. troops have been in Afghanistan.

'When I was a kid, the [Vietnam] war was on TV and it wasn't controlled like it is now,' said Marcia Camacho of Forest Grove, a teacher at Cornelius Elementary School. 'It was in everybody's living room.'

In 2010, Camacho helped organize a panel at the Forest Grove City Library for the No Soy El Army tour. It was part of the Rural Organizing Project, an Oregon coalition of community peace and justice organizations that focused on informing Latino residents about what enlisting in the military entailed.

Camacho said recruiters aren't 'always telling the kids everything they need to know' and that she hoped the panel provided the first-hand information students needed to make an informed decision.

Regular visits

In Gaston, where military recruiters make regular visits to the junior-senior high school, principal Mike Durbin says their efforts have yielded relatively few students who actually sign on. Between 2007 and 2011, only nine seniors selected the military as their next step after high school.

Durbin said he and his staff attempted to curtail recruiters' contact with younger students last year by moving them from the main hallway into a designated classroom. But he insisted that in the end, the school can't ensure they don't talk to seventh and eighth graders.

'We will do everything in our power to keep the younger kids out of the area where the military is,' said Durbin. 'But we can't ban them from coming into the main building.'

Durbin is comfortable with what recruiters are saying to students. 'I honestly believe their message is simply, 'Stay in school, study hard and graduate,'' he said.

But Smith alleges that young pupils in Gaston rub elbows with recruiters long before they start receiving materials from colleges in their junior and senior years of high school. 'By my rough estimation, a student may have contact with a military recruiter approximately 12 times a year,' Smith wrote in a 2010 letter to the Gaston School Board.

A master calendar on the district's website reveals that one recruiter visit, from the Navy, occurred this month, on Jan. 4. The Air Force is set to visit Feb. 16, March 15 and April 19, while the Navy is due to return March 7, April 4 and May 2.

Smith originally met with Durbin and Gaston superintendent Dave Beasley in 2010 to express her grievances with the school's military recruitment policy. At first, she said, they advised her to tell her then 12-year-old son not to go near the recruiters, who were set up in a main hallway and had given him a free hat, a water bottle and a lanyard.

A few months later, Smith was happy to get an unwritten agreement with Durbin and school counselor Richard Ceder that recruiters would refrain from talking to seventh and eighth graders, who are typically 12 and 13 years old. But she took to protesting last week because, she said, that pact broke down when she had an argument with an Air Force recruiter in November.

After a tense meeting with administrators, Smith said she was permitted to be in the room when recruiters visit, but was instructed not to speak.

Forest Grove district policy states that it must must provide military recruiters and colleges with names, addresses and phone numbers of all secondary school students, unless those students or their parents tell the school in writing that they want that information kept private.

Principal Karen Robinson said military recruiters visit FGHS 'no more than once a month' and that, instead of an annual career fair, the school hosts monthly 'multiple college visits' as well as opportunities for internships as they come available.

Military 'selective'

Military recruiters say they're aware of public concerns about their recruiting methods and mission, but counter that they, like colleges, are selective. 'We're not here for people with nothing else to do,' Miller said. 'The Army isn't a last resort anymore.'

Only one-fourth of people age 17 to 24 qualify to enlist, and many who make the cut choose to wait, Miller noted. Even though he's from a military family, Miller himself didn't enlist until he was 30, because he 'just wasn't ready for it.'

Schaffner, who earned her first stripes earlier this month at Camp Johnson, looks at things another way. 'College graduates work in fast food joints now. But with the military, if you qualify, that's pretty good job security,' she said.

source: http://vvvvvv.portlandtribune.com/fgnt/36-news/18053-recruitment-wars

- Editor's note: Katie Sipos, a Pacific University student, wrote this article for a class project last May. The original story was updated for publication this week.

FREMONT, Calif. - Over 100 demonstrators, including many from this city's large Afghan American community, shut down its military recruiting center in a non-violent action March 30 as they protested the

FREMONT, Calif. - Over 100 demonstrators, including many from this city's large Afghan American community, shut down its military recruiting center in a non-violent action March 30 as they protested the  Yesterday, approximately fifty people including students from Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC) along with members of Occupy Wall Street,

Yesterday, approximately fifty people including students from Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC) along with members of Occupy Wall Street,