Jose Palafox -

Until lions have their own historians, histories of the hunt will glorify the hunter. -- African proverb

Introduction: The Border Patrol's "Battle Plan" en la Frontera 1

ON MAY 20, 1997, CLEMENTE BANUELOS, A U.S. MARINE ON AN ANTIDRUG operation, shot and killed 18-year-old Esequiel Hernandez, Jr., in Redford, Texas. Banuelos was a member of Joint Task Force-6 (JTF-6), a federal agency that coordinates antinarcotics operations between the Border Patrol and the military. Although Border Patrol and Marine officials claimed that Hernandez shot at the Marine surveillance team, an autopsy report suggests that Hernandez could not have done so. Banuelos' attorney stated that while Hernandez had no previous criminal history, he fit the profile of a drug trafficker that was given to the marines in their training for missions on the border (Los Angeles Times, 1997). Meanwhile, government officials described the killing as an unfortunate, but justified act of self-defense. "This was in strict compliance with the rules of engagement," said Marine Col. Thomas R. Kelly, deputy commander of the military's anti-drug task force (Katz, 1997: A19).

ON MAY 20, 1997, CLEMENTE BANUELOS, A U.S. MARINE ON AN ANTIDRUG operation, shot and killed 18-year-old Esequiel Hernandez, Jr., in Redford, Texas. Banuelos was a member of Joint Task Force-6 (JTF-6), a federal agency that coordinates antinarcotics operations between the Border Patrol and the military. Although Border Patrol and Marine officials claimed that Hernandez shot at the Marine surveillance team, an autopsy report suggests that Hernandez could not have done so. Banuelos' attorney stated that while Hernandez had no previous criminal history, he fit the profile of a drug trafficker that was given to the marines in their training for missions on the border (Los Angeles Times, 1997). Meanwhile, government officials described the killing as an unfortunate, but justified act of self-defense. "This was in strict compliance with the rules of engagement," said Marine Col. Thomas R. Kelly, deputy commander of the military's anti-drug task force (Katz, 1997: A19).

Three months after the shooting, a grand jury declined to bring charges against Banuelos, despite calls for an indictment by the Hernandez family. Pentagon spokesman Kenneth Bacon defended the decision, saying, "We think Corporal Banuelos was carrying out a lawful and authorized mission, one that was authorized by the Congress of the United States.... He was performing appropriately as a member of the Armed Services in defense of the national interest" (Verhovek, 1997: A8; see also Dunn, 1999a: 264-266).

Family and community members were outraged. "I think somebody should be held responsible for the death of my brother," said Margarito Hernandez. "They made it look like it was his fault. The only mistake he did was to go pasture his goats on that day" (San Francisco Chronicle, 1997: A4). The Redford Citizens Committee for Justice, which included the Hernandez family and border human rights activists, charged that the grand jury included a number of people with strong ties to the Border Patrol and other law enforcement agencies.

Opening Up Borderland Studies: Asking the Epistemological Questions in U.S.-Mexico Border Discourse

The tragedy in Redford was just one example of the "militarization" of the U.S.-Mexico border, a project that began in earnest under President Ronald Reagan and picked up pace under the Clinton administration. To understand the more general militarization of American society, it is imperative to examine the build-up on the border. This article provides a brief overview of the main theoretical and cultural critiques of border militarization. The aim is to encourage writers and activists to examine the many ways in which U.S.-Mexico boundary enforcement and state repression affect the human rights of migrants.

Equally important in understanding the complexities of the militarization of the border as a social phenomenon is the way in which unauthorized migrants, and those living on the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, attempt to make sense of border policing. I examine how border scholars interpret and (re)present the lives of those living in a militarized U.S.-Mexico border and attempt to answer the following questions: What does it mean to argue for the inclusion of narratives of unauthorized migrants whose voices are hardly present in the discourse of border militarization? Can subaltern undocumented immigrants speak in a way that contests and challenges prevailing views of them merely as victims running away from their usually "Third World" countries for political or economic reasons? How can the inclusion of migrants' narratives affect dehumanizing representations of them that previously were framed primarily by policymakers, Border Patrol spokespeople, or by other immigration and border scholars?

As indicated by David Spener and Kathleen Staudt, editors of The U.S.-Mexico Border: Transcending Divisions, Contesting Identities, versions of border discourse differ within the work of social scientists and those working in cultural production. "Version 1 is old-style border studies, grounded in history and the empiricism of the social sciences.... Version 2 is new-style literary studies. Each version seems to know little about the other" (Spener and Staudt, 1998: 14). Indeed, these different versions of border studies reflect not only the variety and multiplicity of borderland(s) studies, but also the borders within traditional academic "disciplines." For Spener and Staudt, such demarcations, "reflect the compartmentalization of our collective intellectual project...as Borderlines pervade our public and private lives, as well as our teaching and academic research" (Ibid.: 5-6).

Finally, why is the militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border occurring when both countries are "embracing" regional economic integration with "agreements" like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)? Is there a relationship between the "opening" of the border for trade and commerce and the "closing" of it to the movement of people?

The next section examines the works of border militarization scholars who have been trained in more "traditional" fields. They include Timothy J. Dunn (sociology), Peter Andreas (political science), Michael Huspek (mass communications), Joseph Nevins (geography), and Christian Parenti (sociology).

I. Social Scientists (De)constructing Borders: Bringing the State Back In?

Timothy J. Dunn and His "Theoretical and Methodological Considerations"

Timothy Dunn, author of The Militarization of the U.S.-Mexico Border, 19781992: Low-Intensity Conflict Doctrine Comes Home, is the premiere theorist of border militarization. As the subtitle explains, Dunn views the border buildup as an example of the repatriation of low-intensity conflict theory and practice to the U.S. Originally developed as a response to guerrilla insurgency in the Third World by the Kennedy administration, low-intensity conflict (LIC) reached its full form during the Reagan administration as a counterinsurgency doctrine in Central America in the early 1980s. Dunn outlines LIC by citing a 1986 U.S. Army Training Report:

Low-intensity conflict is a limited political-military struggle to achieve political, social, economic, or psychological objectives. It is often protracted and ranges from diplomatic, economic, and psycho-social pressures through terrorism and insurgency. Low-intensity conflict is generally confined to a geographic area and is often characterized by constraints on the weaponry, tactics, and level of violence (Dunn, 1996: 20).

Dunn reminds us that although LIC doctrine has been primarily engineered for "third-world settings, it is not devoid of domestic implications for the United States." He argues that many key aspects of LIC have coincided with numerous facets of the militarization on the U.S.-Mexico border (Ibid.: 31). In fact, a report prepared for the Border Patrol's border enforcement efforts was drafted by "planning experts from the Department of Defense Center for Low Intensity Conflict (CLIC) and chief patrol agents from all regions and selected Headquarters staff" (U.S. Border Patrol, 1994: 1, fn. 1).

Given that government officials have portrayed unauthorized migration and illegal drug trafficking from Mexico to the U.S. as a "national security" issue, Dunn argues:

LIC doctrine is the most applicable framework in this regard, given its call for a sophisticated combination of police and military activities to effect social control over targeted civilian populations.... [T]he prospect of some degree of LIC-style militarization in the U.S.-Mexico border region is also worthy of consideration due to its ominous implications for the status of human rights in the borderlands (Dunn, 1996:31).

Although the U.S.-Mexico border region has had a long history of militarism and violence, 2 only in the last few decades has increasing integration of U.S. military armed personnel with civilian law enforcement been documented (see Palafox, 1996: 14-19).

The most provocative and significant section of Dunn's book, an appendix entitled "Theoretical and Methodological Considerations," includes two major theoretical areas of inquiry. The primary one:

concerns the nature of repression in so-called advanced industrial societies, especially those with liberal-democratic systems. A key sub-topic within this focus is the effect of bureaucracy on the status of human rights. The second theoretical area of interest here is actually two related topics: the contemporary world economy and international migration (1996: 186).

A close reading of this section reveals the need for more comparative scholarship in addressing the militarization of the borders and boundaries in other regions of the world where regional economic integration and border enhancement are occurring simultaneously.

Dunn's inquiry into border militarization reveals certain limitations. because the study covers the years 1978 to 1992, it cannot not fully address important political questions, such as the impact of the 1994 NAFTA trade agreements on the contemporary world economy and international migration, or the way in which the Clinton Administration's border policy compares with those of previous administrations covered by Dunn. Moreover, Dunn only briefly draws on certain works by Mexican scholars writing on border militarization (e.g., Juan Manuel Sandoval and Jorge A. Bustamante). More recent works by Mexican scholars on the militarization of the Mexico-Guatemala border and the militarization of law enforcement in Mexico (Lopez, 1996; Fazio, 1996) do reinforce Dunn's argument about the political-economic and territorial needs of the U.S. for stability on the U.S.-Mexico border and within Mexico (see also Weinberg, 2000: 361-307).

There is a clear need for intellectual exchange between scholars on both sides of the border: How do recent political and social events (related to global economic restructuring) in both countries influence the ways in which countries police and maintain social stability? 3 What insights and comparisons can scholars in both countries bring to our discussion of low-intensity conflict on the U.S.-Mexico border and in the southern part of Mexico? How do state practices toward migrants and refugees (in the case of Guatemalan refugees inside Mexico) in both countries correspond and differ? What are the implications for human rights on the Mexico-Guatemala border and U.S.-Mexico border?

Dunn's study of the relationship between enhanced border policing and human rights violations on the border, entitled "Border Enforcement and Human Rights Violations in the Southwest," found that increased border enforcement efforts, post- 1992, have led to an increase in (sometimes hidden) human rights violations in the border region (Dunn, 1999a: 443-451; see also Huspek et al.: 1998). The rise of the militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border during the Carter and Reagan administrations was accompanied by the increased militarization of the police within the U.S.

Despite the groundbreaking nature of Dunn's work, its focus on the physical aspects of border militarization is, according to Jardine (1997: 54), a weakness. The book "focuses almost exclusively on the material characteristics of militarization and generally ignores the ideological and rhetorical aspects (while acknowledging their importance, though)."

Christian Parenti: The Militarized Border Comes Home

Extending Dunn's framework for border militarization, Christian Parenti, in Lockdown America: Police and Prisons in the Age of Crisis, analyzes three aspects of the immigration and naturalization service's internal militarized policing. The first involves an examination of two federal laws that mandate the arrest and deportation of undocumented immigrants and "legal" immigrants who have prior felony convictions. The second involves increased "interagency cooperation" between local law enforcement and the INS, including, in some instances, the "deputization" of police for immigration-related issues. The book's final section deals with the use of high-tech computers and law enforcement intelligence systems that are "mechanisms for tracking, controlling, and intimidating whole populations" (Parenti, 1999: 149). Furthering his argument about this high-tech surveillance panopticon, Parenti draws on Foucault to assert that these new methods of social control will make "the effects of power constant, even while its application is intermittent" (Ibid.: 149). In other words, Parenti continues, "immigrants will fear the law more intensely in that INS/police intelligence systems are automatic, infallible, and instantaneous. The electronic dragnet will force internalization of the INS gaze," forcing migrants even further underground (Ibid.). 4

Parenti briefly examines the INS' "Interior Integrated Enforcement" strategy as an expanded form of low-intensity conflict within the U.S. border. "Border militarization and interior enforcement, like so much of the post-sixties criminal justice buildup, serve as preemptive counterinsurgency," says Parenti (1999:159). As race and class polarization increased with "Reaganomics" in the 1980s, Parenti argues, so too did the need to discipline and punish this "new class of poor and desperate people" (Ibid.: 44). In response to this crisis, created by the elite response to the profit crisis, a new wave of criminal justice crackdowns began.

Though Parenti details recent punitive measures like border militarization and the increasingly militarized immigration raids within the U.S. border, his chapter on border militarization would have benefited from an analysis of the relationship between these political-social control methods on undocumented immigrants to potential social upheaval by this growing population. For instance, why are undocumented immigrants seen as a threat to U.S. hegemony?

In "Urban Warrior Games" (Ibid.: 9: 268, fn. 64), Parenti mentions a series of joint Marine-Navy exercises that took place in Oakland, California, in March 1999, without, however, making possible connections between the increasing race and class polarization of "poor and desperate people" and the militarized policing within the U.S, at its borders, and abroad. 5 For example, although Marine spokespeople for "Urban Warrior" claimed the exercises were intended to enable them to carry out "humanitarian" and "disaster relief" aid abroad and within the United States, closer examination reveals that the Marines were more concerned with maintaining and expanding U.S. imperial hegemony in an increasingly unstable and polarized world.

In examining "today's emerging anticrime police state and prison-industrial complex" (ibid.: 4), Parenti's work raises an interesting question: Do recent militarized policing and prison building reflect the strength or weakness of the state's ability to maintain social order and stability? Although border militarization and militarized policing might suggest a strengthening of the state, and especially its ability to suppress and control marginalized communities, it could also expose the vulnerability of late capitalism. Within the logic of U.S. economic restructuring and the need to "take advantage of new markets" lies a contradiction. In seeking to maximize profits and relocate production outside the U.S., many working people -- especially in the inner cities -- have been rendered economically superfluous. In City of Quartz, Mike Davis (1992) shows how policing and imprisonment have increasingly substituted for job creation and local development in large areas of inner-city Los Angeles, where people of color and immigrants live. Instead of seeing Los Angeles as a city in need, many local authorities view these urban areas, and the people living in them, as potential threats to the established order.

Peter Andreas: Borderless Economies/Barricaded Borders and Image Projection on the U.S.-Mexico Border

In their devastating critique of the costly and deadly "war on drugs," Drug War Politics: The Price of Denial, Peter Andreas and his co-authors show that the "war" on illicit drugs and drug-related crime actually exacerbates addiction, abuse, and "crimes" related to this underground economy. As Andreas and his colleagues point out, much of what we fear and condemn as drug-related crime is in fact the product of our drug policies, not the substances themselves (Bertram et al., 1996: 34).

Similarly, Andreas successfully shows how "free-trade" market liberalization policies and increased economic integration with Mexico have fueled legal and "illegal" economic flows between both countries (see also Massey and Espinosa, 1997: 991-992). Indeed, while much of the discourse among policymakers focuses on how "free trade" facilitates legal trade and commerce, Andreas tells us that:

an unintended side effect of liberal economic reforms in Latin America (deregulation, privatization, and the opening up of national markets) has been to encourage the export of illegal drugs and migrant labor. This can partly be explained by simple economic logic: opening the economy through market liberalization reduces the ability of the state to withstand external market pressures -- and the high market demand for illegal drugs and migrant labor in the U.S. is certainly no exception (1995: 6; see also 1998a: 206-207; 1996: 55).

Before the passage of NAFTA, U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno claimed that once passed, NAFTA would help "protect our borders" and that, a failure to pass it would make "effective immigration control...impossible." This assertion is contradicted by documents Andreas obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. According to pre-NAFTA Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) studies, the increased entrance of Mexican trucks could "prove to be a definite boon to both the legitimate food industry and drug smugglers who conceal their illegal shipments in trucks transporting fruits and vegetables from Mexico to U.S. markets" (Andreas, 2000: 75).

Andreas' work (1994: 46) has suggested that the practice and ideology of market liberalization (e.g., NAFTA) might superficially appear to be a "retreat of the state" and a form of boundary erosion, but in reality increased militarization and cross-border economic flows on the U.S.-Mexico border suggest something else. thus, it can be argued that a new function of borders in a global economy might actually be to simultaneously "open" and "close" border(s) between countries. on the U.S.- Mexico border, Andreas argues, recent enforcement "has less to do with actual deterrence [of unauthorized migrants] and more to do with managing the border's image and coping with the deepening contradictions of economic integration" (1999a: 14, emphasis added).

Andreas (1998b: 353) even argues that border policing is a spectator sport, though the objective is to pacify rather than to inflame the passions of the spectators. His insightful examination into how recent border militarization has gone about "recrafting" an image of control on the border encounters problems, though, by limiting investigation of border militarization to the perceptions of the spectators (Congress, the media, local residents in the border areas, and the broad public). This position does not consider the effects of border militarization on the human rights of undocumented immigrants and fails to see the agency of immigrants. Analogies that reduce the process of undocumented immigration (in the context of a militarized U.S.-Mexico border) to "an endless game of cat-and-mouse" or "hunted vs. hunter" (Ibid.; see also Kossoudji, 1992: 159-180) problematically construct and view undocumented immigration only from the perspective of "the hunters" (see Hagan, 1998: 357-361).

For human rights groups like the Arizona Border Rights Coalition, documenting and challenging the abuses visited on undocumented immigrants by Border Patrol agents also includes monitoring the recent vigilantism by local ranchers toward would-be migrants near the Nogales and Douglas border area. Ironically, Andreas' line of argument, that U.S. border enforcement policy is flawed and not serious about thwarting unauthorized migration, is also used by anti-immigrant groups, such as the Nogales, Arizona-based "Neighborhood Ranch Watch," in their efforts to apprehend, detain, and turn "illegal" immigrants -- sometimes at gunpoint -- over to local law enforcement (see Palafox, 2000: 28-30). This discussion leads us to the work of Michael Huspek, who examines border enforcement strategies such as Operation Gatekeeper in San Diego, California.

Michael Huspek: Operation Gatekeeper, or the Cultural/Economic Logic of State and Citizen Production in the Age of Globalization

With the implementation of Operation Gatekeeper in October 1994, would-be migrants found that the San Diego-Tijuana border became increasingly difficult, though not impossible, to cross. As border enforcement increased in one area, migrants rerouted their entry attempts to the eastern parts of San Diego. Whether the INS intended Operation Gatekeeper to be "a de facto agent of business" (Kahn, 1997: M1), Michael Huspek suggests, in Production of State and Citizen: The Case of Operation Gatekeeper(1997: 19), that Gatekeeper's effect on immigrant-dependent businesses was to create a shift in the type of worker gaining entry into the U.S. that amounts to a strengthening of the labor pool available to u.s. employers, while at the same time restricting access to those who would most likely use the state's social programs. Like Andreas, Huspek argues that Gatekeeper allows the state to hoodwink the public without in any way damaging the interests of capital (Ibid.: 3).

Joseph Nevins: Political Geography, the Social Construction of the "Illegal," and the Racialization of Space

In Joseph Nevins' important work (1997: 8; see also Nevins, 2000) on the rhetorical and ideological ways in which the media represent "illegals," he argues that the term "illegal" is a new and problematic way of looking at unauthorized migrants because it designates the migrant as a criminal. "as such, the `illegal' is subject to a whole host of practices legitimated by the full weight of the law." Whereas a wide variety of terms previously described undocumented immigrants (e.g., "wetbacks," "undesirables," and "illegitimate"), Nevins argues that the state's emphasis on the "illegality" of undocumented immigrants is closely tied to the role of nation-states and national boundaries in an increasingly globalized economy. Border enforcement measures like Operation Gatekeeper should be considered in this larger context. Nevins suggests that:

the principal actor in this performance of territorial boundary construction is the state. The goal of the actor is the maintenance and strengthening of the nation. Globalization's challenges to national boundaries lead efforts to protect the uniqueness of the nation against alien forces. Gatekeeper is but one such effort. Therefore, the globalized state -- apart from being a gatekeeper -- is also a political territorial entity whose principal functions are to provide security, largely against real and imagined alien forces (1998: 370).

Unlike many of the previous border scholars, Nevins correctly notes the racialization of immigration (both in discourse and practice). "We cannot divorce the growing emphasis on `illegal aliens' from the long history in the united states of largely raced-based anti-immigrant sentiment rooted in fear and rejection of the `other'" (Ibid.: 236). According to Nevins, Operation Gatekeeper is a manifestation of such sentiment. Although his study goes beyond an analysis of undocumented immigration discourse, his section on Operation Gatekeeper could have benefited from an examination of the connections between the growing economic integration in the San Diego/Tijuana region and the emphasis on the "illegality" of unauthorized migrants. 6

II. Cultural Workers and Cultural Studies: History, Truth, Subjectivity, and the Challenge to the U.S.-Mexico Border Master Narrative

Jose David Saldivar, in Border Matters (1997: ix), incorporates recent border theories in an attempt to build a Cultural Studies that challenges the homogeneity of U.S. nationalism and popular culture. Although Border Matters does not primarily address the militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border, Saldivar does show how some aspects of LIC doctrine can be interpreted through the lens of cultural production.

Using novels, corridos, short stories, poems, ethnographies, essays, paintings, performance art, and music, Saldivar humanizes terrain that can be left emotionally abstract by social scientists. For example, in his chapter, "The Border Patrol State," he explores how Native American novelist Leslie Marmon Silko was detained in New Mexico at a border checkpoint by the Border Patrol. Saldivar also brings a sexual orientation in his reading of gay Chicano writer John Rechy's the miraculous day of Amalia Gomez. Saldivar suggests that Rechy not only contests racism, sexual oppression, and homophobia, but also "dramatizes how the government's doctrine of low-intensity conflict spills over into the lives of everyday people." Saldivar also points out that the lyrics to "Jaula de Oro" (The Gilded Cage) by the norteno group Los Tigres del Norte might hint at the "fear and anxiety" of undocumented immigrants in the United States when they sing: "What good is money if I am like a prisoner in this great nation? When I think about it, I cry. Even if the cage is made of gold, it doesn't make it any less a prison" (Ibid.: 113, 5).

In reading Border Brujo, the work of performance artist Guillermo Gomez-Pena, Saldivar begins to explore the multiple meanings of alienation. He notes that Border Brujo thematizes "a relationship between capitalism and schizophrenia" (Ibid.: 158; Deleuze and Guattari, 1977). Deleuze and Guattari have undoubtedly deeply influenced Gomez-Pena's work. yet it is a mistake to suggest that as a consequence, "we can no longer conceptualize the U.S.-Mexico border self as `alienated' in the sense that Marx defined it, because to be alienated in the classic sense presupposes a coherent self rather than a scrambled, `illegally alienated' self" (Saldivar, 1997:158). this is to overlook Gomez-Pena's direct involvement in political action at the San Diego/Tijuana border area.

In his article, "Death on the Border: A Eulogy to Border Art," Gomez-Pena tells us that his performance art group, TAF/BAW, was initiated in 1984 so as to create a dialog between artists, activists, and intellectuals from Mexico and the U.S. (see Gaspar de Alba, 1998: 218). They view themselves as part of a "binational collective that combined critical writing, site-specific performance, media, and public art with direct political action...on both sides of the border" (Gaspar de Alba, 1998: 218, emphasis added). Gomez-Pena depicts the border in very colorful terms. For him it is "a region of political injustice and great suffering.... The border remains an infected wound on the body of the continent, its contradictions more painful than ever" (Siems, 1994: 22).

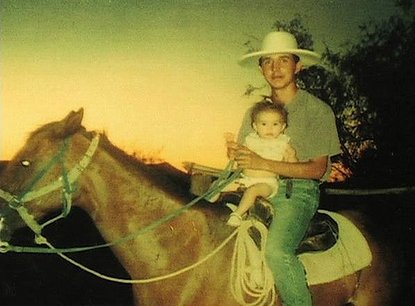

Some unfortunate experiences have led Gomez-Pena to call California "a police state for Latinos" (Ibid.: 28). In a period of two months in 1994, Gomez-Pena was detained several times by law enforcement officials in San Diego for walking around his neighborhood with his boom box, for stealing his own radio, and, another time, for failing to answer a summons that was issued while he was away. Gomez-Pena also was dragged out of bed at 7:00 A.M. and handcuffed in front of his son and wife for supposedly being a drug dealer.

The incident Gomez-Pena will never forget, though, is the time when he and his son spent 45 minutes in police custody after Gomez-Pena was accused of stealing his son. After eating breakfast with his wife and his then-four-year-old son (who happens to be fairly blond), Gomez-Pena decided to go for a walk in a park with his son, only to be stopped by a policeman. As it turned out, two blond women from the restaurant had called 911 to report that a Latino man and a "suspicious-looking woman" were in a cafe with a boy "who didn't look like he belonged to them," and "who was clearly being held against his will." Gomez-Pena later recalled that:

In many ways it was a kind of baptism.,. It made me aware of the current climate in California, of the resurgence of this virulent xenophobia. I realized that I was coming back to a country that's in a state of emergency, and I was going to have to be in a constant state of alert. I really felt my own fragility, and the fragility of my own son (Siems, 1994: 27-28).

Though Gomez-Pena is careful to note the racism and cultural antagonisms between Anglos and Chicanos/Latinos on the borderlands, he also implicates the media and anti-immigrant legislation in the rise of violence against the Chicano/Latino population. In his chapter "The '90s Culture of Xenophobia: Beyond the Tortilla Curtain," in The New World Border: Prophecies, Poems, and Loqueras for the End of the Century, Gomez-Pena tells us that:

What begins as inflammatory rhetoric eventually becomes accepted dictum, justifying racial violence against suspected illegal immigrants. What Operation Gatekeeper, Proposition 187, and SOS [Save Our State] have done is to send a frightening message to society: The governor is behind you; let those "aliens" have it. Since they are here "illegally," they are expendable.... To hurt, attack, or offend a faceless, and nameless "criminal" doesn't seem to have any legal or moral implications (Gomez-Pena, 1996: 69).

Since there is little scholarship on the history of anti-immigrant groups like Light Up the Border and other vigilante groups that have been active in the border area for the past few decades, 7 one must appreciate Gomez-Pena as a "chronicler of history." 8 Similarly, the few studies on the effects of media coverage of undocumented immigration on public opinion (Simon and Alexander, 1993; Wolf, 1988) allow us only to speculate that an atmosphere of violence toward migrants and vigilantism on the border is encouraged by media coverage of immigration issues that portrays the border as overrun. An example is Light Up the Border, so named because they shined their car headlights toward the border to call attention to undocumented immigration. It was formed in 1989 by Muriel Watson, the widow of a former Border Patrol agent, based on twisted local media coverage. She explained that the participants shared her concern: "they all had [newspaper] clippings: `Oh, look at this, this 16 year old was raped and her throat was slit and they rescued her just in time....' So this was what motivated me...pure and simple" (Gutierrez, 1996: 259).

Challenging this caricature racism is Gloria Anzaldua's classic, Borderlands/La Frontera (1987). She reminds us that it is not only "male workers" who cross the border; undocumented women also "illegally" cross la frontera. Through autobiographical and historical interpretation, she contests the given "truths" in "objective" historical interpretations of the "borderlands" as male-centered and Eurocentric. In her careful reading of Borderlands/La Frontera, Sonia Saldivar-Hull points out that as Anzaldua "chronicles the history of the new Mestiza, [she] explores issues of gender and sexual orientation that Chicano historians like David Montejano, Arnoldo De Leon, and Rodolfo Acuna have not adequately addressed" (Saldivar-Hull, 1991: 212; see also, Saldivar-Hull, 2000: 59-79). What Saldivar-Hull suggests is of great importance, because even while we engage with subaltern history, we need to be conscious, as Robin Kelly (1996: 13) reminds us, to look "way, way, way below, to the places" scholars traditionally miss. In using nontraditional sources like poetry, prose, and autobiography as a way of writing history, Anzaldua reconceptualizes the meaning of "history." "Oral history is not only a tool or a method," Asian American historian Gary Okihiro tells us, "it is also a theory of history which maintains that the common folk and the dispossessed have a history and that this history must be written" (Okihiro, 1984: 206, emphasis added).

According to Anzaldua, the "U.S.-Mexican border es una herida abierta [is an open wound] where the Third World grates against the First and bleeds" (1987: 3), thus reminding us of inequalities that exist in the U.S.-Mexico border. "Learning about their poverty," says Luis Alberto Urrea (1993: 2) of the people forced to live in the trash dumps of Tijuana, Mexico, "also teaches us about the nature of our [U.S.] wealth." In a global economy where inequalities between and within countries are ever increasing, inquiries into how, and for what, we do research have important consequences for the borderlands and those living on the margins of borders.

Remaking Border Social Analysis: Ongoing Contentions in Field Research

Scholars in ethnic studies need to cross academic borders between the "traditional disciplines" (e.g., history, sociology, political science, etc.) and newer interdisciplinary fields like Chicano studies and ethnic studies. Our scholarship is constantly questioned and challenged for not being "objective," for being "politically" driven, and even for "disuniting America." 9 The master narrative in American history, or what Chicano studies historian Rodolfo F. Acuna calls "the American paradigm," sets up boundaries between what is considered "true" and "objective," and what is not. For Acuna, the:

study of history and other social sciences in the U.S. is determined by a small body of scholars who define what is the proper subject of inquiry and what qualifies as scholarship. In this way they establish a hegemonic view and, under the banner of scholarly objectivity and truth, dismiss the historical memory of scholars such as myself who do not accept their paradigm (Acuna, 1998: 8).

In agreement with the "organic intellectual," Acuna challenges the American paradigm that calls for "objectivity." I, too, refuse this paradigm and, instead, argue that borderland scholars can and must do more than interpret the world; they can and should attempt to change it. What are the implications for activist-scholars like Acuna and myself in doing such work? Who is our scholarship for? What do we do with this scholarship? The questions and implications for the scholars, their work, and the people they are "studying" should be explored.

In the course of doing field research on the border, I have often been puzzled by the following question: What is the role of the researcher when an informant asks for help in getting across the border? In her essay on field research with marginalized communities, sociologist Maxine Baca Zinn (1979: 279) offers insight. "My direct involvement with informants," says Baca Zinn, "did not always further the goals of the research, but it was `essential to alter the exploitative relationships which research imposes....' direct participation in the research does sharpen the researchers' sense of obligation to the people they are studying."

Jose Palafox, (This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.) is a graduate student in the Department of Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. Palafox, born in Tijuana, B.C., Mexico, and raised in San Diego, California, has long been involved with border and immigrant rights groups. This is part of the author's doctoral dissertation tentatively titled: "The Open Veins of Undocumented Workers: Enforcing Global Apartheid Through U.S.-Mexico Border Boundary Policing, 1992-2000."

NOTES

1. This term was used by Rahm Emmanuel, a former Clinton administration assistant, who stated that support from the armed forces for law enforcement along the U.S.-Mexico border is "consistent with their mandate in protecting national security" (Branigin, 1996: A26).

2. Chicano historian David Montejano (1999: 256, fn. 43) argues that in "a historical sense, the U.S.-Mexico border, as a creation of war between these two countries, has always been militarized." See also Rodolfo Acuna (2000: 41-56).

3. According to Bailey and Quezada (1996: 3), "possible future points of bilateral tension [between the U.S. and Mexico] include...heightened control, even militarization, of the border region arising from anti-drug and immigration policy."

4. Parenti(1999: 160) does mention that the targeting of undocumented Latinas and their "social networks" by immigration authorities "serves to disrupt and generally undermine Latino communities... [and thus] damages the future of political mobilization and the crucial preconditions for political organizing and thus becomes pre-emptive counterinsurgency." Grace Chang's work (2000: 216), for example, attempts to show how anti-immigrant sentiment and punitive legislation targeted at undocumented immigrants has given rise to resistance movements within immigrant communities. Chang argues that anti-immigrant discourses and practices have at times "served to galvanize people of color and immigrant communities rather than suppress them. As one observer put it, `[Proposition 187] inadvertently triggered the political awakening of many Latinos who saw themselves, regardless of their citizenship status, as being targets. In Los Angeles, with its emerging Latino majority, Proposition 187 inspired one of the largest protest demonstrations ever -- activism that eventually translated into growing Latino political participation.'"

5. One should note that the U.S. Marine Corps' handbook on "Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief" (a guidebook for "Urban Warrior") includes "Migrant Camp Operations," where law enforcement potentially receives military assistance "when non-U.S, citizens arrive at (or are brought to) U.S. territories for processing as potential refugees" (U.S. Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory, 1999: 26). For an insightful work on the relationship between U.S. foreign policy in Central American during the 1980s and the "immigration crisis" that the Reagan administration helped to create, including its plan to round up and incarcerate thousands of "suspected terrorists" at that time, see Kahn (1996).

6. Recognizing that there is no extensive study of regional economic integration in the San Diego/Tijuana area in the post-NAFTA era, the essays in Tardanico and Rosenberg (2000) provide insights into our examination and comparison of the political, economic, and geographic areas in the U.S. and Mexico.

7. For an insightful analysis of how the activities of vigilante and anti-immigrant groups in San Diego should be viewed in a context of the U.S. government's border enforcement strategy, see Novick (1995:171-181; and Dwyer, 1994:118-119). Recently, a group of migrant workers in North County San Diego were shot, beaten, and robbed near their campsite by white supremacist youths; a 17-year-old immigrant from Oaxaca was beaten to death in the same area. See Wilberg and Sanchez (2000).

8. This is Jose D. Saldiar's characterization of the Mexican American activist-scholar, Ernesto Galarza. Quoted in Garcia (1994: 23).

9. Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. (1991), denounces multiculturalism as a "cult of ethnicity" that is separating U.S. society rather than integrating it. For a critique of this view, see Ronald Takaki (1994: 296-299).

REFERENCES

Acuna, Rodolfo

2000 Occupied America: A History of Chicanos. New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

1998 Sometimes There Is No Other Side: Chicanos and the Myth of Equality. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Andreas, Peter

2000 Border Games: Policing the U.S.-Mexico Divide. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

1999a "Borderless Economy, Barricaded Border." NACLA: Report on the Americas 33,3: 14-21.

1999b "Smuggling Wars: Law Enforcement and Law Evasion in a Changing World." Tom Farer (ed.), Transnational Crime in the Americas: An Inter-American Dialogue Book. New York: Routledge: 85-98.

1998a "The Paradox of Integration: Liberalizing and Criminalizing Flows Across the U.S.-Mexican Border." Carol Wise (ed.), The Post-NAFTA Political Economy: Mexico and the Western Hemisphere. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press: 201-220.

1998b "U.S. Immigration Control Offensive: Constructing an Image of Order on the Southwest Border." Marcelo Suarez-Orozco (ed.), Crossings: Mexican Immigration in Interdisciplinary Perspective. Cambridge: Harvard University Press: 343-356.

1996 "U.S.-Mexico: Open Markets, Closed Border." Foreign Policy 103 (Summer): 51-69.

1995 "The Retreat and Resurgence of the State: Liberalizing and Criminalizing Flows Across the U.S.-Mexico Border." Paper presented at the Meeting of the Latin American Studies Association, the Sheraton, Washington, D.C. (September 28 to 30).

1994 "The Making of Amerexico: (Mis)Handling Illegal Immigration." World Policy Journal 11 (Summer): 45-56.

Anzaldua, Gloria

1987 Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Bailey, John and Sergio Aguayo Quezada

1996 "Strategy and Security in U.S.-Mexican Relations." John Bailey and Sergio Aguayo Quezada (eds.), Strategy and Security in U.S.-Mexican Relations Beyond the Cold War. San Diego: University of San Diego Press: 1-15.

Bertram, Eva, Morris Blachman, Kenneth Sharpe, and Peter Andreas

1996 Drug War Politics: The Price of Denial. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Branigin, William

1996 "U.S. Beefing Up Forces on the Southwestern Border." Washington Post 12 (January).

Chang, Grace

2000 Disposable Domestics: Immigrant Women Workers in the Global Economy. Cambridge: South End Press.

Davis, Mike

1992 City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. New York: Vintage.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari

1977 Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. New York: Viking Press.

Dunn, Timothy J.

1999a "Border Enforcement and Human Rights Violations in the Southwest." Christopher G. Ellison and W. Allen Martin (eds.), Race and Ethnic Relations in the United States: Readings for the 21st Century. Los Angeles: Roxbury Publishing: 443-451.

1999b "Military Collaboration with the Border Patrol in the U.S.-Mexico Border Region: Inter-Organizational Relations and Human Rights Implications." Journal of Political and Military Sociology 27,2: 257-277.

1996 The Militarization of the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1978-1992: Low-Intensity Conflict Doctrine Comes Home. Austin, Texas: CMAS Books.

Dwyer, Augusta

1994 On the Line: Life on the U.S.-Mexican Border. London: Latin America Bureau (Research and Action).

Fazio, Carlos

1996 El Tercer Vinculo: De la Teoria del caos a la militarizacion de Mexico. Editorial Joaquin Mortiz.

Garcia, Mario T.

1994 Memories of Chicano History: The Life and Narrative of Bert Corona. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gaspar de Alba, Alicia

1998 Chicano Art: Inside/Outside the Master's House, Cultural Politics and the CARA Exhibition. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.

Gomez-Pena, Guillermo

1996 The New World Border: Prophecies, Poems, and Loqueras for the End of the Century. San Francisco: City Lights.

Gutierrez, Ramon A.

1996 "The Erotic Zone: Sexual Transgression on the U.S.-Mexico Border." Avery F. Gordon and Christopher Newfield (eds.), Mapping Multiculturalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press: 253-262.

Hagan, Jacqueline

1998 "Commentary." Marcelo M. Suarez-Orozco (ed.), Crossings: Mexican Immigration in Interdisciplinary Perspective. Cambridge: Harvard University Press: 357-361.

Huspek, Michael

1997 "Production of State and Citizen: The Case of Operation Gatekeeper." Unpublished manuscript. California State University, San Marcos.

Huspek, Michael, Roberto Martinez, and Leticia Jimenez

1998 "Violations of Human and Civil Rights on the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1995-1997: A Report." Social Justice 25,2:110-130.

Jardine, Matthew

1997 Book Review. Z Magazine (January): 52-54.

Kahn, Robert S.

1997 "Keeping Illegal Workers Male, Young, and Fit." Los Angeles Times (July 6).

1996 Other People's Blood: U.S. Immigration Prisons in the Reagan Decade. Boulder: Westview Press.

Katz, Jesse

1997 "A Good Shepherd's Death by Military." Los Angeles Times (June 21).

Kelley, Robin D.G.

1996 Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class. New York: The Free Press.

Kossoudji, Sherrie A.

1992 "Playing Cat and Mouse at the U.S.-Mexico Border." Demography 29,2: 159-180.

Lopez A., Martha Patricia

1996 La Guerra de Baja Intensidad en Mexico. Mexico, D.F.: Universidad Iberoamericana.

Los Angeles Times

1997 "Marines Stand by Comrade in Border Death Inquiry." August 15.

Massey, Douglas S. and Kristin E. Espinosa

1997 "What's Driving Mexico-U.S. Migration? A Theoretical, Empirical, and Policy Analysis." American Journal of Sociology 102,4: 991-992.

Montejano, David

1999 "On the Future of Anglo-Mexican Relations in the United States." David Montejano (ed.), Chicano Politics and Society in the Late Twentieth Century. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press: 234-257.

Nevins, Joseph

2000 "The Law of the Land: Local-National Dialectic and the Making of the United States-Mexico Boundary in Southern California." Historical Geography 28: 41-60.

1998 "California Dreaming: Operation Gatekeeper and the Social Construction of the `Illegal Alien' Along the Boundary." Unpublished dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles.

1997 "A Borderline Crime: Operation Gatekeeper and the Construction of the `Illegal.'" Paper presented April 24, 1997, at the Annual Meetings of the Association of Borderlands Scholars in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Novick, Michael

1995 White Lies, White Power: The Fight Against White Supremacy and Reactionary Violence. Monroe: Common Courage Press.

Okihiro, Gary

1984 "Oral History and the Writing of Ethnic History." David K. Dunaway and Willa K. Baum (eds.), Oral History: An Interdisciplinary Anthology. Nashville: American Association for State and Local History: 195-211.

Palafox, Jose

2000 "Arizona Ranchers Hunt Mexicans." Z Magazine (July/August): 28-30.

1996 "Militarizing the Border." Covert Action Quarterly 56 (Spring): 14-19.

Parenti, Christian

1999 Lockdown America: Police and Prisons in the Age of Crisis. London: Verso.

Saldivar, Jose David

1997 Border Matters: Remapping American Cultural Studies. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Saldivar-Hull, Sonia

2000 Feminism on the Border: Chicana Gender Politics and Literature. Berkeley: University of California Press.

1991 "Feminism on the Border: From Gender Politics to Geopolitics." Hector Calderon and Jose David Saldivar (eds.), Criticism in the Borderlands: Studies in Chicano Literature, Culture, and Ideology. Durham: Duke University Press: 203-220.

San Francisco Chronicle

1997 "Civil Rights Probe for Cleared Marine: He Killed Goatherd on the Border." August 16.

Schlesinger, Jr., Arthur

1991 The Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society. New York: Norton.

Siems, Larry

1994 "Just Who Does He Think He Is?" Reader 23: 16-32.

Simon, Rita J. and Susan H. Alexander

1993 The Ambivalent Welcome: Print Media, Public Opinion, and Immigration. Westport: Praeger Publishers.

Spener, David and Kathleen Staudt (eds.)

1998 The U.S.-Mexico Border: Transcending Divisions, Contesting Identities. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Takaki, Ronald

1994 "At the End of the Century: The `Culture Wars' in the U.S." Ronald Takaki (ed.), Different Shores: Perspectives on Race and Ethnicity in America. New York: Oxford University Press: 296-299.

Tardanico, Richard and Mark B. Rosenberg (eds.)

2000 Poverty or Development: Global Restructuring and Regional Transformations in the U.S. South and the Mexican South. New York: Routledge.

U.S. Border Patrol

1994 Border Patrol Strategic Plan: 1994 and Beyond, National Strategy (July).

U.S. Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory

1999 "Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief." X-File 3-35.11. Quantico. January.

Urrea, Luis Alberto

1993 Across the Wire: Life and Hard Times on the Mexican Border. New York: Anchor Books.

Verhovek, Sam Howe

1997 "No Charges Against Marine in Border Killing." New York Times (August 15).

Weinberg, Bill

2000 Homage to Chiapas: The New Indigenous Struggles in Mexico. London: Verso.

Wilberg, Elizabeth and Leonel Sanchez

2000 "Latino Workers Shot, Beaten by a Group of Men." San Diego Union-Tribune (July 8).

Wolf, Daniel

1988 Undocumented Aliens and Crime: The Case of San Diego. San Diego: Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies. Monograph No. 29.

Zinn, Maxine Baca

1979 "Field Research in Minority Communities: Ethical, Methodological, and Political Observations by an Insider." Social Problems 27,2:209-219.

Source: http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/palafox.html