Brian Montopoli | Washington City Paper, January 31, 2003

Career Day, Cardozo High School. First session. Marine recruiter Sgt. Derrick Sanders is making his pitch.

"Good morning, class," he says. The students respond weakly. Sanders stands straight, raises his voice, and repeats himself. This time the students offer him a "Good morning" in return, almost in unison.

"Good morning, class," he says. The students respond weakly. Sanders stands straight, raises his voice, and repeats himself. This time the students offer him a "Good morning" in return, almost in unison.

The Marine Corps, he tells them, is for the hard cases: the ones who want to be first in the fight, the ones who can handle the hellish, relentless boot-camp experience at Parris Island. Not to mention the ones who need an education—the Marines will pay for college, assuming you're willing to take your classes at night. Sanders harps on the money factor, but he never gets away from the idea that the Marine Corps is about more than just finances.

"You don't join for the money," he says. "You join for the pride of belonging."

Sanders, who is black, has an easy rapport with the Cardozo students, most of whom are minorities. He tells the kids that "a lot of 'em said I wouldn't make it [in the Marines], how it was too hard," and he lets his presence—as well as his spotless uniform, which is bedecked with gold buttons and gleaming medals—tell the rest of the story.

As Sanders is finishing his presentation, the kids, who have grown comfortable with him, get to the really important stuff: his haircut. One girl asks,"Does everybody have those high-top fades?" Sanders laughs and says, yeah, pretty much. He wraps up by telling the students that he has enlistment information with him and that he'll be available after class if any of them want to talk. Then, with a smile, he walks to the side of the room.

Another man is waiting by the door. After Sanders yields the floor, he ambles to the front of the room and stretches his organization's banner across the blackboard. The students aren't quite sure what to expect, but they soon discover that this man has a different agenda. Instead of pushing them toward a particular career, he seems intent on guiding them away from one.

"Do you enjoy being bossed around?" asks one of the man's pamphlets. "Do you want someone consistently telling you what to do and how to do it? If your answer is 'no,' you might have a hard time adapting to military life."

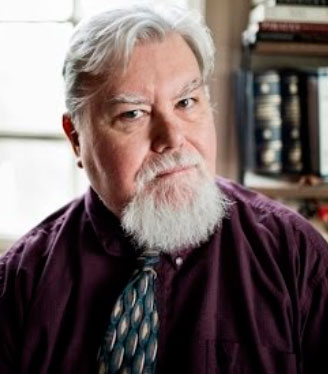

"My name is John Judge," he says, "and I'm here to talk to you about some of the things you'll come up against in the military."

Judge tells the students that the military is fundamentally racist—not to mention sexist, out to exploit the poor, and institutionally committed to robbing people of their freedoms. He says that a disproportionately high percentage of African-Americans end up on the front lines during wartime. He tells them that minorities rarely rise through the military ranks. And he cites numerous reasons why they shouldn't enlist—including the high incidence of rape in the military and the low percentage of military jobs transferable to civilian life. He backs it all up with rhetoric sharpened at dozens of settings just like this one.

"You know what 'GI' stands for? 'Government issue,'" Judge says. "They own you 24/7, and there isn't anything you can do about it. You go where they want you to go, and have to do what they tell you to do. They make you give up your basic rights. If you get a sunburn, they can court-marshal you for damaging military property."

Sgt. Sanders watches from the side of the room. His hands are clasped together in front of his body, right below the belt buckle on his uniform. His face is blank. After a few minutes of listening to Judge talk about how easily people can be kicked out of the military, Sanders raises his hand.

"What would be a reason someone would get discharged from the military?" he asks. He seems to be trying to show the students that Judge—who is white, overweight, wearing a long goatee, and 55 years old—doesn't know what he's talking about.

"All sorts of reasons," says Judge, who looks as if he's handled the question before. "Objection, hardships, administrative, early outs, honorable...The list goes on."

Sanders persists. "If you do something wrong, you get punished, correct?" he says. "You smoke marijuana, you get punished."

"In the military," Judge responds, "just talking back to an officer is a crime."

Sanders nods. Once Judge finishes discussing the shortcomings of the military, he talks to the students about finding alternate careers—one pamphlet mentions jobs in "electrical wiring"—and refers them to other sources of money for college.

Sanders does not talk for the rest of the period. Later, when asked about Judge, he says, "Everyone is entitled to their opinion." (Well, not everyone: Sanders admits that even if he had agreed with certain parts of the presentation, he could not have said so, because the military does not allow such criticism from within its ranks.)

Judge is the voice of military dissent in D.C. public schools, a longtime armed-forces critic who shows up at career days in scruffy brown cords to spread his anti-enlistment gospel. His materials are a bit tattered and his facts are sometimes questionable, but Judge's mission is clear: to provide what he calls "an alternate viewpoint" to that of the military's advocates in the schools. For his efforts, he's attracted the vitriol of angry recruiters, had his materials stolen from under his nose, and been kicked off high-school campuses. America may now be preparing for war, but Judge has been battling recruiters, administrators, and military brass for decades.

Judge has always found a way to keep things interesting. As a freshman at the University of Dayton in 1965, Judge resented having to take the required Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) course. Administrators would not let him drop the class, but he let them know his position by attending peace vigils wearing his ROTC uniform. After newspapers carried a photo of him protesting in uniform, Judge caught the ire of the administration.

"They tried to kick me out of the school," he says. "They gave me psychological evaluations." The school didn't expel Judge, but neither did it release him from ROTC duty. Administrators eventually made a special exception to allow Judge to attend the ROTC class wearing a suit and tie, to keep him from attending protests in uniform.

Judge grew up in Falls Church, Va., an only child with a mother who went from pacifist to war supporter during World War II. She worked at the Pentagon for more than 30 years, crunching numbers to project how many people would be called into the draft during a war. When Judge was 15, his mother suggested that he get a job in the Pentagon library. He turned down her offer, saying he didn't want to work there, and she didn't force the issue; she had taken note of his evolving political views, and she didn't want to pick a fight.

Judge's father was a different story. He also worked at the Pentagon, as a loading-dock supervisor, and he wanted his son to go to business school; when Judge seemed to be headed in a different direction, he did his best to shape his son's thinking.

"I would be watching The Twilight Zone or something, and he'd come downstairs and turn the TV to wrestling or Westerns," says Judge. "He said that was more realistic."

Judge's father tried to teach him to fight when he was 10, but he refused to learn. Their differences would become more pronounced as they got older, until his father died, when Judge was 17. "We weren't very close," Judge says. "It was pretty emotionally cold. If he hadn't passed away, it would have become a very stormy relationship."

At the age of 18, Judge attended training with the American Friends Service Committee, where he learned to be a draft counselor, essentially a paralegal who understood military law and could advise people on how to avoid or delay being drafted. He eventually got out of his ROTC class at Dayton, and he became increasingly politically active on campus, passing out petitions and starting an alternative newspaper that he would slip under students' doors at 3 in the morning so that it wouldn't be confiscated. At age 20, with the Vietnam War in full swing, Judge started counseling GIs who had fled the military about their AWOL status.

Judge gradually got used to the downside of his political activism, which included physical threats from war supporters and the taunts of administrators. During his senior year, Judge says that the dean of students called him into his office to offer him mock sympathy.

"It must be pretty lonely out there," said the dean, telling Judge that his anti-war position had alienated him from the rest of the student body. But this was the late '60s, and Judge wasn't feeling very lonely. He looked at the man and said, "I probably have more friends than you do." Judge and some of those friends eventually occupied administration offices and helped eliminate Dayton's mandatory ROTC program. Once he graduated, he stuck around campus to continue the fight, although many of his peers moved on.

"A lot of people from my generation tried to carry on their values, but it isn't easy," says Judge. "People take their own paths. I just figured, with my mom having worked in the Pentagon for 30 years, I should do my part to balance out the family karma."

As Judge's work as a counselor—he eventually got $45 per week from the student government for his efforts—brought him into contact with more frustrated veterans, he became determined to get his information into public schools. Judge believed that military recruiters were drafting impressionable kids without really explaining to them the consequences of enlistment, and he wanted to bring his point of view to the high-school classroom. But in Dayton, where he lived, the schools wouldn't let "counter-recruiters" in. He needed a place where he could get access to the students, whether administrators liked it or not.

So, in 1981, he came home.

In the early '80s, activists were putting pressure on the D.C. school board to ban Junior ROTC (J-ROTC) programs in public schools, according to media reports. So, Judge says, the school board offered a compromise: It would allow counter-recruiters into the classroom to provide an alternative viewpoint to that of the pro-enlistment ROTC programs. Judge took advantage of the decision to found his organization, CHOICES (Committee for High School Options & Information on Careers, Education and Self-Improvement), and begin talking to D.C. school kids about the racism, sexism, and repression of civil rights that he believes are part of the military lifestyle.

Judge had it tough in the early going. When he went to Anacostia High School for his first-ever campus visit, a guidance counselor, who had come across Judge's materials, intercepted him before he was able to talk to any students.

"I understand you're giving people a radical message," Judge recalls the counselor as saying. He made Judge and a friend wait in the principal's office until a ROTC instructor arrived.

"You gentlemen are going to have to leave campus," the man said. Judge protested but ended up losing the fight. He drove straight to the school-board offices, where he pleaded his case for equal access to the classroom. After a few phone calls, Judge was reinstated, and he was back on campus by the end of the day.

Although military types routinely wax wistful about protecting the American way of life, they often seem to need refresher courses on the First Amendment. At Ballou High School last year, for example, Judge was assigned to speak to a classroom of J-ROTC students. After he talked for a couple of minutes, the colonel watching the proceedings spoke up.

"I've listened to this for a couple minutes," he said, as Judge recalls the incident, "and I don't think my students need to be here for it." He then told the students that they were excused.

At Luke Moore Academy in 2001, Judge returned to a classroom to find that his materials had gone missing. When he started asking where they had gone, an angry ROTC instructor came up and said, "Are you attacking my Army?" Judge later found his handouts in the trash.

At a recent career fair at Eastern High School, Judge laid out information for the students to examine. This time, a recruiter a few tables away didn't even bother to wait until Judge wasn't looking.

"She came over, picked up one of my brochures without even reading it, and said, 'This is propaganda,'" says Judge. "Then she just began to gather up handfuls of my materials—whole piles. I told her I'd rather she didn't take my stuff—I wanted to give it out to the students. She said she would give them to the students herself. Then she walked back to her table and stuffed them in her briefcase."

Judge's pamphlets look like holdovers from an earlier time: One features an ominous gas mask and the phrase "The Military's Not Just a Job...It's Eight Years of Your Life!" Another features a cartoon under the heading "Dead End Jobs" and a graphic explaining the number of blacks in the Army prison population in 1977. Judge offers students a hodgepodge of anti-military rhetoric: fact sheets on escaping the delayed-entry program, quotes alleging slow promotions because of institutional racism, and bar graphs showing data on the low percentage of black Army officers.

"I'm reaching out to kids and trying to help them make an informed decision," he says. "Not hearing anything negative about the military isn't preparing kids to face the real world. They get a lot of messages that they don't have a future, and they turn to the military because it's the path of least resistance. We ought to be giving them some sense of hope and letting them know they have options."

He likens his efforts to those of a consumer-watchdog group.

"What I do is just provide information that people don't otherwise get," says Judge. "I'm sure Ford doesn't like that Consumer Reports puts them in some sort of category. But for the consumer, it's vital."

Cherine Foty, a junior at Wilson High School, says recruiters need a watchdog. "We're constantly bombarded with recruiting stuff—from J-ROTC being [at Wilson], from the recruiters calling our houses," she says. "It's extremely important that we get his perspective so people don't make a one-sided decision."

Actually, a one-sided decision is nearly inconceivable with Judge's perspective in the mix. Judge's idealism assails the very foundations of military life. He resents the fact that new recruits are "stripped of their identity," for example, and he doesn't like the military's use of fear as a motivator. If soldiers have a moral obligation to think before taking an extreme action, though, officers need to have their orders followed swiftly if their units are to function effectively.

In Judge's ideal world, enlistees would have the right to give their superiors guff as well as to unionize—changes that would make the U.S. armed forces no more reliable than the French transit system. Judge, however, believes that foreign fighting forces have provided evidence that the U.S. military command structure need not be so rigid.

"The idea that we couldn't have a less repressive military model is just silly," he says. "There's this logic that takes the state of the military as a given—'If we have to exploit rights, so be it.' But it's during a war that you have to give people a chance to say no."

As a recent Department of Defense paper points out, however, Judge's quest to inform the students relies, in part, on misconceptions. Judge tells kids that blacks are disproportionately represented on the front lines. In fact, blacks are underrepresented in combat: They make up 21 percent of the enlisted force but only 15 percent of combat forces, and are generally concentrated in administrative jobs. Largely because of this distribution, blacks made up 23 percent of military personnel but just 17 percent of casualties during the Gulf War. And while Judge pushes alternatives to military life for the students, he neglects to mention that, according to Department of Defense statistics, African-Americans in the military make more money and are better educated, on average, than their civilian counterparts.

Judge, though, makes valid points on other key data. Though minorities make up 35 percent of the armed forces, they account for just 8 percent of its officers at the ranking of O-7 and above—generals and admirals. And it's even worse for women of color than their male counterparts: There is not one minority female among the armed forces' 159 officers with O-9 or higher rank—three- and four-star generals, and their Navy equivalents—and there are only 32 women and four minority women among its more than 700 O-7 and O-8s. Judge's claim of a glass ceiling is supported by the Defense Department's own data, as is his argument that, despite recruiters' promises, many enlistees never end up graduating from college.

Ellen Barfield, a 46-year-old Army veteran who sometimes accompanies Judge when he goes into schools, says that she was shielded from the realities of military life when she enlisted, in 1977. She says that the military isn't always as collegial as it appears in brochures, and expresses bitterness that the military did nothing when she suffered an attempted rape while serving her country.

"I wish someone had been there when they started, to tell me the way things were," she says.

Sgt. Charles Mooney, however, a former Olympic boxer and 22-year Army veteran, says Judge needs to get up to date on the past few decades of military history.

"I just don't think it's positive for [Judge] to be here," says Mooney, an Army ROTC instructor at Eastern High School. "This isn't the place for it. If it wasn't for [soldiers], we might not have our freedom. We don't need him and his propaganda in here. I don't need him coming in here and telling me about what happened to my black parents. That was then; this is now. We had times when blacks were used, but we are more advanced now. The military instills discipline and structure for kids who might not have a father figure. There's nothing wrong with that."

Army Col. Joseph E. Nickens, the J-ROTC director for the D.C. public schools, says he is not particularly worried about Judge.

"We have daily contact with the students, so the guy doesn't affect us much," he says. "Our instructors hold their ground. We ignore him. The people that would listen to him aren't on our team anyway. People who are with us, who are patriotic, aren't paying attention to what

he has to say."

Up until the late '60s, a program similar to J-ROTC called the National Defense Cadet Corps was required of all males in D.C. public schools. At that time, according to Eastern graduate and labor organizer Roger Newell, Eastern was able to field a corps of more than 1,000 young men, all of whom wore uniforms their families were required to buy. Newell says that students who refused to participate were suspended, and that, in some cases, school administrators would subsequently inform the draft board that the suspended students had forfeited their student draft deferment. Newell claims that some of those students were quickly shipped off to Vietnam. Thanks to a lawsuit, the city eventually stopped requiring participation in the National Defense Cadet Corps, and enrollment plummeted. The J-ROTC program rose in its place years later. But J-ROTC is not mandatory, and, according to Joy White, a media officer for the Navy, it is not meant to socialize students into the military.

"This is more of a citizenship program," she says. "It's not a recruitment tool. Junior ROTC teaches students the importance of giving back to the community. It instills in them a sense of personal responsibility and accomplishment."

Judge scoffs at White's claim.

"It's disingenuous to claim it's not a military recruiting program," he says. "Statistically, people who spend time in J-ROTC programs are much more likely to enlist—20 to 25 percent. It's a military social club. They claim to teach discipline, but it's not self-discipline. It's obedience."

Whatever you call it, it's an option parents often embrace. When Forestville High School, a public school in Prince George's County, announced in 2001 that it would become Forestville Military Academy, the school had a waiting list months before it opened its doors. And though no District schools make ROTC mandatory for all of their students, there are Army J-ROTC programs in 12 D.C. schools, as well as Navy and Air Force J-ROTC programs in four more. At Cardozo, according to Assistant Principal Barbara Childs, all of the ninth-grade students enroll in the program, though it is technically not mandatory.

"[J-ROTC] is a great program—you learn leadership, physical fitness, discipline, and how to drill," says Luis, a 10th-grader at Cardozo who wants to join the Air Force. "It really brings out the best in you. Most of [my classmates] don't like it, though—they don't have time because they work, and they don't like wearing the uniform."

Luis often shows up at 6:30 a.m. to do drills with his ROTC instructor, and he and a small contingent of ROTC students periodically engage in drill-team competitions. The ROTC students' uniforms are lent to them free of charge during the school year, and they are not charged for most of their travel.

ROTC Cadet Col. Wayne Logan, a Dunbar senior, is the student leader of J-ROTC in D.C. He has already entered the Army's delayed-entry program and is hoping to attend West Point, and argues that Judge doesn't appreciate the value of ROTC programs and the military for D.C. students.

"He doesn't understand what he's talking about," says Logan. "He's on the outside looking in. ROTC is really important for a lot of the students—it helps them be leaders. You won't rob a bank in [an ROTC] uniform."

Logan and Judge see eye to eye on one issue, however: the potential conflict with Iraq.

"I don't think we should go," says Logan. "But if I'm serving in the military, it's my responsibility to go because of my commitment to this country. I live in a pretty rough neighborhood in D.C.—there are gunshots almost every day. If I'm gonna die, I'm gonna die. I'd rather die for a cause."

In 1999, the Army got congressional approval to expand its J-ROTC program at a rate of roughly 50 schools per year over five years, up to a total of 1,645 schools nationwide. At the time of the announcement, Army Secretary Louis Caldera said that the program was necessary, in part, because "fewer and fewer Americans ever have served in uniform." Judge worries that the increased presence of J-ROTC programs in the schools will make it increasingly difficult for his relatively rare visits to have an impact.

"The J-ROTC guys are in there every day," says Judge. "Sometimes they don't even tell me when there's a career day coming up."

Lt. Col. John Hawkins, an Army veteran and ROTC instructor at Dunbar, says that Judge's concerns are overblown.

"I get maybe 300 to 400 kids per year [in the J-ROTC program]," he says, "and of those, probably less than 5 percent end up in the military."

He also dismisses Judge's charges of racism in the armed forces.

"The military has been one of the ways that African-Americans have been able to move into the middle class in this country," says Hawkins. "If you compared the state of race issues in the military to the civilian population—well, I think the military comes out on top. It's much more fair and much more colorblind."

Over the years, Judge has fought a number of forces to get his message across—skeptical principals, nasty military brass, and uncooperative school boards. Recently, though, he has acquired a new nemesis: the Bush administration's No Child Left Behind Act, which includes a provision that forces schools to give the names, addresses, and phone numbers of juniors and seniors to military recruiters. If a school fails to comply with the new requirement, it can lose its federal funding. Parents have the right to opt out of the program, but Judge says that many parents do not know that this is the case.

"The military already has constant access to the students through the J-ROTC program," says Judge, "and this goes even further. They're saying that they want the same access to students that the colleges have, since there are schools that don't currently let recruiters in. But if we hold the military to an equal-access rule, then they should only be able to come in on career days, like everybody else—not have J-ROTC programs and recruiters who park in the counselors' offices year round."

The military's recruitment woes have been well publicized: Just 25 percent of students now say they plan to join the military, down from 32 percent a decade ago. Relatively low unemployment rates and an increase in college enrollment have nearly doubled the amount of money it costs the military to attract one recruit today as compared with 10 years ago. Recruiters say they have little choice but to pursue more invasive tactics to make up for their increased costs and decreased candidate pool.

"[Recruiting] is a business," says Sgt. Blondine Maddox, an Army J-ROTC instructor at Eastern who was a recruiter for more than eight years. "It's like sales. You show them what you have to offer is what they want, and then they'll buy. No Child Left Behind will make that job easier—instead of just talking to them at the high schools, at malls and football games, you'll have a list of their home numbers."

Dante Furioso, a senior at Wilson, says, "On two occasions I've gotten calls from people trying to recruit me. The guy didn't introduce himself as having anything to do with the military—he just started talking about scholarships. Then he started asking my height and weight, stuff like that, and I started getting a little uncomfortable. Finally, at the end, he told me he why he was calling."

Furioso says that Judge's voice is one of the few helping students understand their options beyond military life.

"No one's called me to offer a non-military-related scholarship," he says. "There's a lot of pro-military sentiment out there, and I don't think students think about the long-term effects of joining the military. [Judge's] giving another point of view is really important and really honorable."

According to Marine Corps officials, Marine recruiters make more than 1 million phone calls each year. Maddox says that each recruiter is, on average, responsible for two to three contracts per month, and that recruiters who fail to meet their quotas are sent to remedial training. The military may trumpet the fact that it is an all-volunteer force, but most of those volunteers don't realize they want to lug around 80-pound packs until a recruiter gets in touch with them.

Judge remembers a time when the recruiters' jobs were far easier.

"In the 1980s," Judge says, "the career days were abysmal. I'd show up and there would be five military tables, somebody from the [recreation] center, the beauty salon, maybe the phone company, and that was about it."

The economic expansion of the last 20 years has changed all that: At the Cardozo career fair where Judge and Sanders square off, there are representatives of more than 25 industries present, including the fire department and public defenders' office. For many military recruiters, the easiest students to attract are those whose bad behavior or poor academic performance has kept them from taking advantage of these increased opportunities.

"If we didn't help send some of these kids to college, they'd end up flipping burgers," says Army recruiter Sgt. James Turton. "We get these kids off the street and into something secure."

In conversation, Judge alternates between easygoing and intense; he'll reminisce about his college days before breaking into a 20-minute monologue about the president's justification for war. His earnestness sometimes generates ideas that sound great in theory but awful in practice. On classroom visits, for example, Judge offers to accompany any student who is planning to enlist on his visit with the recruiter. No one has ever taken him up on the offer.

Judge estimates that he probably speaks at about 10 schools each year, every time one has a career day. He spends much of the rest of his time working as a fundraising consultant to nonprofits such as the Washington Peace Center and the Quixote Center, as well as doing other "anti-militarism work" and publishing papers on political assassinations that have made him popular with conspiracy buffs. Judge has a hard time providing concrete numbers as to how many students he has kept out of the military, but he says that his information has an impact on their future decisions.

"It's hard to say how many kids I've actually steered away—a few kids have come and talked to me, and I helped a few get out of the delayed-entry program," says Judge. "All I know is that I make an impact with the kids."

"CHOICES is a shoestring operation," says Barfield. "It's not glossy. It's not shiny. The equation is pretty lopsided—the recruiters have the money and the time. You don't often hear 'Thanks a lot for helping me.' You just have to have faith that the results will show up long-term."

Judge's campaign requires something of a unique combination: an individual with unrelenting idealism and a municipality that makes it possible to disseminate anti-military sentiment in public schools. In many ways, Judge is far more alone now than when the dean provided him with mock sympathy back in college.

"Of course I get frustrated at times," says Judge. "But this has always been a passion for me. You can't just throw your hands up."

When Judge attends political meetings, he is often the oldest person in the room. Many of his friends have moved on to work or families that leave little time for the battles Judge spends his days fighting. But just like the recruiters, he believes wholeheartedly in his mission, and he says he won't ever stop showing up in local schools, even if his interactions with authority figures continue to be contentious.

"For most people, these kids in D.C. are throwaways," he says. "A lot of people don't seem to think they have a future. I just want them to know that they have options." CP

Source: http://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/news/article/13025903/uncle-scram

###